by Marilyn Muir, LPMAFA

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

For most of mankind’s existence, justice was a vague process, usually determined by “might is right” or tribal rule that grew up in towns, cities, countries governed by monarchy and dynasty or dictatorial rule. Attempts by mankind to bring about a more democratic process where individuals counted equally and had personal and civil rights have emerged through the centuries only to have surged and then failed as mankind drifted back into the old habit of unequal rights and rules. When the U.S. Founding Fathers attempted to persuade the British monarchy to allow for personal rights and fair judgments, monarchy fought back (as monarchy does) to shut down the citizens’ rights to dissent and fair hearings and representation. What started as simple protest ended as civil war between those who believed in the crown and its rights to rule and those who believed in freedom for all. This conflict became the Revolutionary War as our forefathers fought for freedom and liberty so they could enjoy those rights and pass them down through the centuries – all the way to us in 2020.

The Founding Fathers led the war and the Framing Fathers built on that victory to give us a form of government that would preserve what had been won, including a framework to protect those rights and the fledgling country, our U.S. Constitution. These patriots were the politicians and leaders of the original colonies and were used to calling the shots for their territories. These leaders attempted to negotiate, conciliate and build a government to which they all could agree. It was a win some / lose some negotiation since not all issues could be settled. Perhaps it wasn’t perfect, but it was the best they could do with what was available. They did expect that the generations to follow would take up what didn’t get resolved, such as slavery. They trusted that future citizens would preserve what had been so hard won by the brave patriots of that time and by the generations that followed.

The Framing Fathers chose a tri-partite form of government, three branches that could have checks and balances on one another, to preserve and protect the country and the Constitution, and to ensure the safety and continuance of that government through the generations that followed. The Legislative (House of Representatives and Senate were two components collectively known as Congress), the Executive (President) and the Judicial (system of courts). Basically, the House was representative of the citizens. The Senate was the solution to the States’ Rights issue of that time. The Judicial was to be the check and balance for the Executive branch.

A judiciary had not existed in any constant form up to that time, but the Framers were determined to address the screaming need for a fair and impartial judiciary and rights of citizens. As the discussions went forward, the tripartite form was established that included the format for an impartial judiciary plus they authorized a citizens’ Bill of Rights. The 1787 Constitutional Convention had embedded the judiciary as Article III of the Constitution that took effect Mar 4, 1789. The judiciary was the first law passed by our First Congress by September 21, 1789 and was immediately signed into law September 24th by President George Washington… the birth of the Supreme Court of the U.S. (SCOTUS). The mandate was fair and equal justice for all, following the framework laid out in the Constitution. The Bill of Rights was appended to the Constitution itself the following day. That’s how important those functions were to our fledgling government.

Immediately after signing the Judiciary act into law, President George Washington nominated these justices to serve on the court: John Jay as Chief Justice, and John Rutledge, William Cushing, Robert H. Harrison, James Wilson, and John Blair, Jr. as associate justices. All six were confirmed by the Senate on September 26, 1789. Harrison, however, declined to serve. In his place President Washington nominated James Iredell, who was confirmed by the Senate. No times of birth were available:

- John Jay, born December 12, 1745, NYC, NY (NY)

- James Wilson, born September 14, 1742. Carskerdo, Scotland (PA)

- John Rutledge, born September 17, 1739, Charleston, SC (SC)

- William Cushing, born March 1, 1732, Scituate, MA (MA)

- John Blair, Jr., born April 17, 1732, Williamsburg, VA (VA)

- James Iredell, born October 5, 1751, Lewes, England (NC)

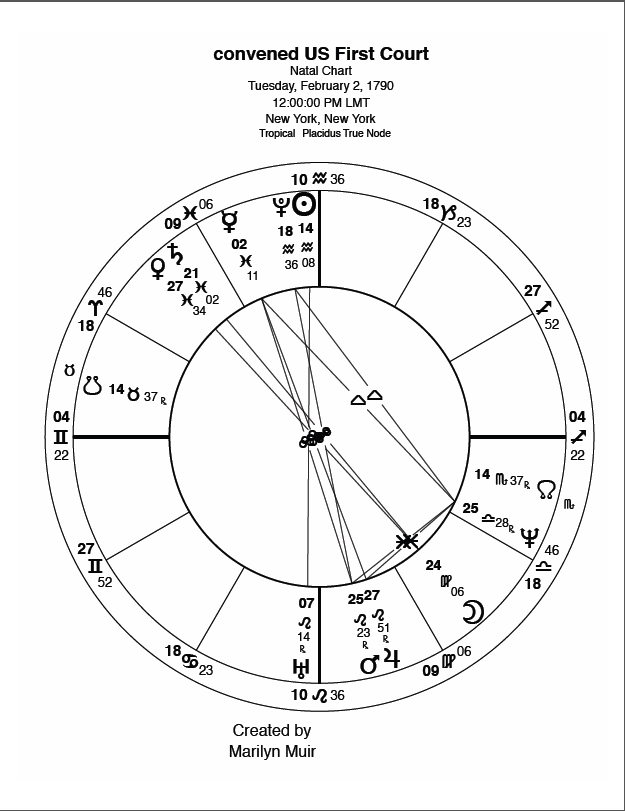

SCOTUS convened their first court: February 2, 1790 no time given LMT, NYC, NY. The inaugural session was February 2-10, 1790 at the Royal Exchange, New York City. At that time, New York City was the capital of the U.S. The earliest sessions were organizational proceedings, with first cases not heard until 1791. In 1790 the national capital including SCOTUS moved to Philadelphia, initially meeting at Independence Hall; later the court was established at City Hall.

After George Washington’s two presidential terms, John Adams became our second president. In 1800, Adams lost his re-election bid to Thomas Jefferson. They were bitter rivals, as were their parties. A power struggle ensued at the end of Adams’ term before Jefferson’s inauguration. Adams and the Federalist Party engaged in political maneuvering by the appointment of John Marshall to Chief Justice in order to deny Jefferson his SCOTUS appointment, plus the Federalist Party reduced the court from six to five to further deny Jefferson a judicial appointment. The ensuing political battle resulted in the House impeachment of an unpopular justice, but the Senate acquitted him in 1805. Sound familiar? To me this political nonsense defeats the purpose of the judiciary for the fair and impartial justice they all fought so hard to win and to set in stone in the Constitution.

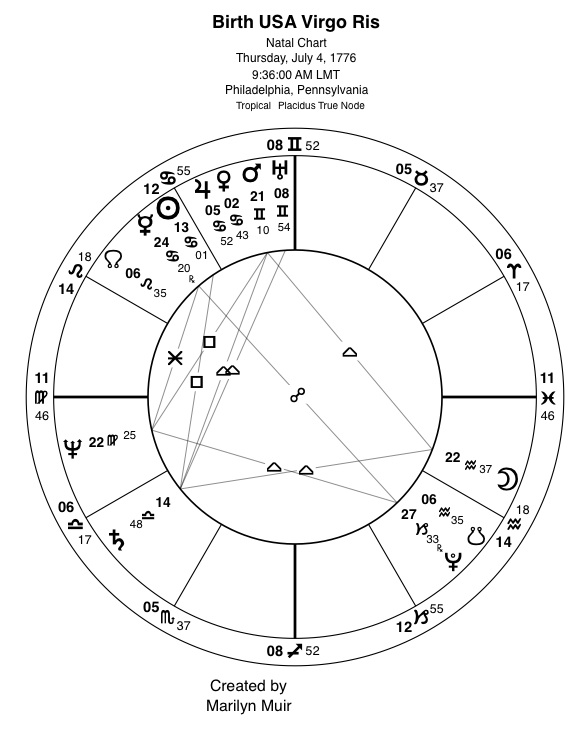

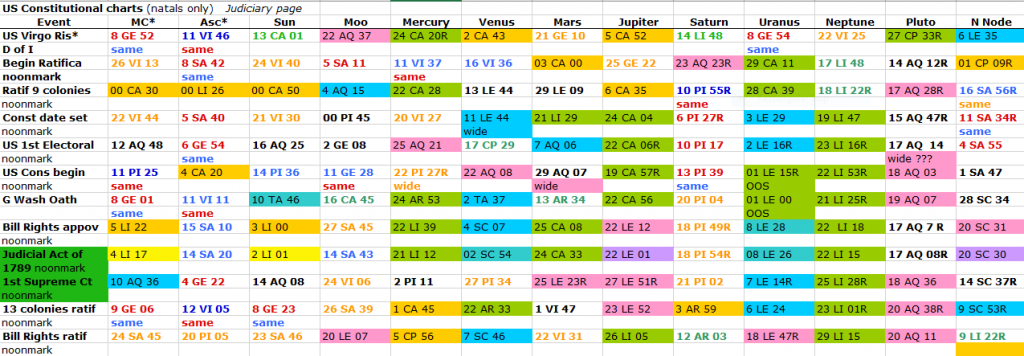

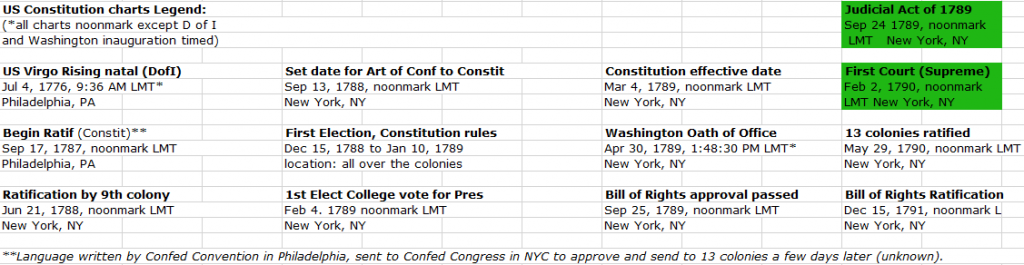

The judiciary is a declared branch of the Constitutional government and ties tightly to the March 4, 1789 beginning, but dates are all within a few months which offers limited reading. I chose as base the Declaration of Independence chart that leads and ties strongly to the beginning of the Constitution. My U.S. chart of choice is the Declaration of Independence (D of I): July 4, 1776, 9:36 AM LMT, Philadelphia, PA.

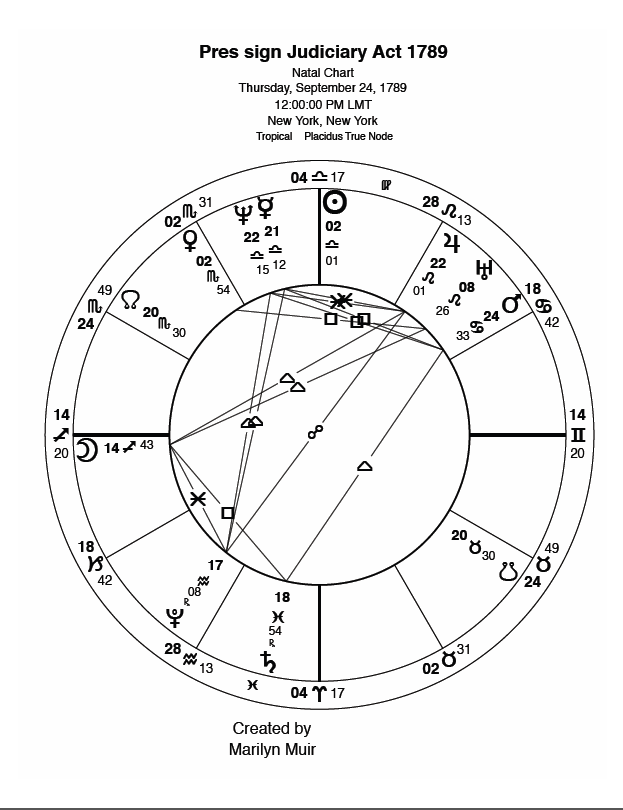

Astrologically, we have a choice for the base SCOTUS chart: the day the Judiciary Act was signed into law: September 24, 1789 or the first meeting of our Supreme Court (SCOTUS): February 2,1790, both events were in New York City. Business hours are traditionally 8 AM to 4 PM, so noonmark is the preferred chart. Still this material is speculative because we do not have actual time of day.

Mental notes*:

1) Know that noonmark Midheavens and Ascendants can be substantially off twelve hours in either direction, with the Moon also moving approximately one degree every tq9ew-ruo hours on the day’s clock.

2) Also remember that because it is a noonmark chart, the Sun is always close to the Midheaven. Don’t read too much into this conjunction until you have time to verify any noonmark chart.

Judicial Act of 1789 natal chart highlights

- Midheaven 4:17* Libra conjunct Sun 2:01.

- Ascendant 14:20* Sagittarius conjunct Moon 14:43* square Saturn 18:54R Pisces.

- Mercury 21:12 Libra conjunct Neptune 22:15, both square Mars 24 Cancer 33, both trine Pluto 17:08R Aquarius.

- Venus 2:54 Scorpio square Uranus 8:26 Leo.

- Jupiter 22:01 Leo opposed Pluto 17:08R Aquarius, both square N Node 20:30 Scorpio.

First SCOTUS Court natal chart highlights

- Midheaven 10:36* Aquarius, conjunct Sun 14:08 and Pluto 18:36,

both closely square lunar nodes 14:37 Scorpio (N) / Taurus (S). - Uranus 7:14R Leo conjunct I.C., opposed Midheaven*.

- Mars 25:23R Leo, Jupiter 27:51R widely opposed Pluto 18:36 Aquarius.

- Moon 24:06 Virgo* opposed Venus 27:34 Pisces and Sat 21:02.

How are these charts connected to the US Declaration of Independence birth chart?

(5˚orb, hard aspects)

- Judicial Sun and Midheaven* square DI Venus 2:43 and Jupiter 5:52 Cancer.

- Judicial Moon* and Ascendant* square DI Ascendant 11:46 Virgo.

- Judicial Saturn opposed DI Neptune 22:25 Virgo, both square DI Mars 21:10 Gemini.

- Judicial Mercury and Neptune square DI Mercury 24:20R Cancer and Pluto 27:33R Capricorn (T-square).

- Judicial Uranus conjunct DI N Node 6:35 Leo, both square Judicial Venus 2:54 Scorpio.

- Judicial Pluto 17:08R Aquarius widely conjunct DI Moon 22:37 opposed Judicial Jupiter,

and all square Judicial N Node.

- 1st Court Midheaven* widely conjunct DI S Node 6:35 Aquarius.

- 1st Court Pluto conjunct DI Moon 22:37 Aquarius both opposed Inaugural Mars 25:23R and Jupiter 27:51R Leo.

- 1st Court Saturn and Venus opposed DI Neptune 22:25 Virgo.

- 1st Court Ascendant* conjunct DI Midheaven and Uranus 8:52-4 Aquarius.

- 1st Court Uranus conjunct DI N Node 6:35 Leo.

- 1st Court Moon* 24:06 Virgo conjunct DI Neptune 22:25Virgo.

- 1st Court Neptune 25:28R Libra square DI Mercury 24:20R Cancer and Pluto 27:33R Capricorn.

The charts are from 1776 and 1789 (2) and are so specifically interconnected, there is no mistake. The D of I lives on through the Constitution and its Bill of Rights and SCOTUS. This lays the base for us to examine the current SCOTUS justices in our next study. Stay tuned.

Submitted for publication in AFA Today’s Astrologer Fall, 2020, republished with slight editing.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.