Research notes from Astrologer Marilyn Muir

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Airship disasters are quite different from airplane crashes. In 2015 I stumbled across an article on the crash of the Airship Roma and started collecting bits and pieces of information. As I work on multiple researches over long spans of time, some get put together as specific projects and published and some end up in my research files, unfinished for whatever reason, with the plan to “get back to them” at some time in the future. It is my intention to make much of this astrological research available to other astrologers for their use in their personal research projects. I will be adding those mostly incomplete files to the research section of my website as I am able to assemble them into some reasonable order. For example, last week I posted my quite extensive research on the Tulsa Race riot on the website. Following is what started my file on Airship Disasters.

Email from me (Marilyn Muir) to AFA March 5, 2015

{Because I have written a large number of articles for the AFA bulletin.}

Look at what I found in Sunday’s headlines.

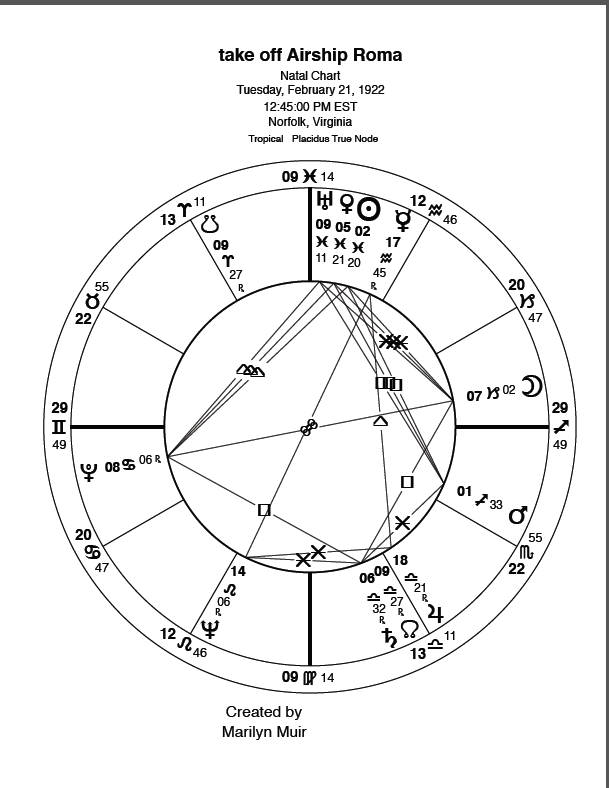

First the article that gave me time of day (sort of) and location. That is the take off airship chart.

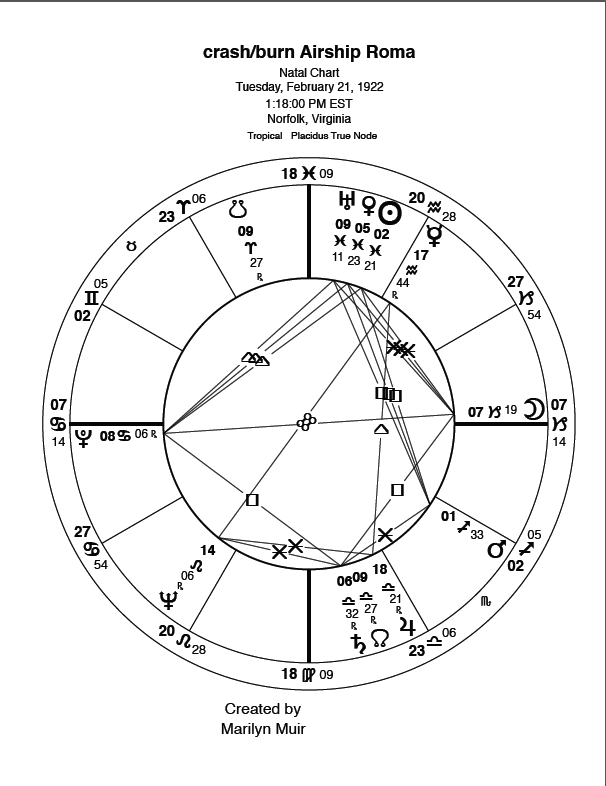

If I am not mistaken the crash/burn occurred just prior to the speculative crash/burn chart I erected.

The airship rose slowly, started forward, started to lose air across the top, started to collapse, fell onto electrical wires, the hydrogen exploded, it burned until evening.

43 died, 8 escaped, 3 without a scratch. They never fully left the field of the takeoff. 33 minutes on the clock seems like a long time but look at the aspects.

Uranus is on the MC of the takeoff chart, quincunx the N Node. First Uranus then Pluto transit square on the Moon/angle.

The Moon/Pluto opposition reaches the Asc/Dec axis by 1:18 pm (33 minutes) and that is square those nodes (they keep showing up in these catastrophe charts).

The description of what happened sounds like Armageddon.

I’m not sure I can do more with this because the available articles are quite repetitive and don’t add much insight. Just interesting! Marilyn

Several of my old files would not load the websites so I Googled for backup and replacements:

2021 list Hydrogen Airship Disasters

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_airship_accidents

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hindenburg_disaster

http://www.zeppelinhistory.com/zeppelin-facts/airship-accidents/

https://www.ranker.com/list/blimp-disasters/jacobybancroft

https://www.archives.gov/exhibits/eyewitness/html.php?section=5

https://www.britannica.com/story/the-hindenburg-before-and-after-disaster

https://hindenburg.fandom.com/wiki/Hydrogen_Airship_Disasters

Airship Roma disaster

By Richard Riis

Fifteen years before the crash of the Hindenburg galvanized the nation and effectively put an end to lighter-than-air commercial travel, the fate of the Roma made headlines – and then was forgotten. Built in Italy in 1919, the Roma‘s speed, payload and range had drawn attention throughout Europe before the airship was purchased in 1921 by the United States Army Air Service for $200,000, the equivalent of $2.6 million in 2015 dollars.

The Roma was enormous – 410 feet long, 92 feet tall – and capable of carrying 100 passengers and cargo at speeds of up to 80 miles per hour. The airship was designed for trans-Atlantic crossings and was the largest semi-rigid airship in the world at the time.

The semi-rigid airship was a cross between a zeppelin, those cigar-shaped airships with a light metal skeleton beneath a fabric skin, and a blimp, which depends on pressurized gas within its skin to maintain its form. The Roma lacked a skeleton, but its 1.193 million cubic foot gasbag was held somewhat in shape by a metal-ribbed nose cap and an articulated keel that ran along the bag’s underside, from nose to tail. Within the keel were housed the control room, navigation space, passenger cabin, the outriggers on which the engines rode, and, fastened to the back, a box kite-like construction that served as the ship’s rudder and elevator. In addition to the eleven cells of hydrogen within its skin, the airship housed six cells of air into which additional air could be pumped if the gasbag were to droop or flatten.

The Roma made its first flight in the United States from Langley Field, in Norfolk, Virginia, on November 15, 1921.

Three months later, at 12:45 p.m. on February 21, 1922, 45 men, including the crew, a few civilian mechanics, and government observers, boarded the Roma at Langley for a short demonstration flight. One hundred fifty men gripped lines holding the airship to earth as the airship’s six engines were fired up. The lines released, the Roma pitched upward then leveled off.

At an altitude of 500 feet, Captain Dale Mabry of the Army Air Service, the airship’s skipper, ordered cruising speed and the Roma began making for Chesapeake Bay. Upon reaching the Bay, Mabry ordered the ship south along the shoreline. The crew waved to people below at Fort Monroe and at a crowd of spectators watching the awesome spectacle from the government pier.

At Willoughby Spit, the Roma headed out over the water toward the Norfolk Naval Station. One thousand feet above the Naval Station, crewmembers noticed that the upper curve of the gasbag’s nose was flattening. The nose of the Roma began to pitch downward at a 45-degree angle. As the stress on the airship increased, the keel began to buckle, and the tail assembly began to shake loose.

Captain Mabry turned the Roma away from the Naval Station and toward the open water. The passengers and crew tossed a shower of equipment and furniture from the keel’s windows to lighten the ship’s load. But nothing could stop the Roma’s rapid descent. The airship plummeted toward an open field alongside the Station’s depot – and a high-voltage electric line.

As the Roma’s nose struck the ground, the enormous gasbag brushed the electric line, and in an instant the skin of the enormous airship was engulfed in flame. The eleven gas cells, loaded with more than a million cubic feet of hydrogen, exploded in a colossal fireball. Amidst a rain of fire and debris, sailors and depot workers rushed to the wreckage, only to be driven back by the heat and flames. Three fire companies spent five hours battling the blaze. When the smoke cleared and the twisted metal wreckage cooled, thirty-four bodies were recovered from the remains of the Roma. Amazingly, eleven individuals on board survived, three of them completely unharmed.

The crash of the Roma marked the greatest disaster in American aeronautics up to that time. The Army launched an inconclusive investigation into the accident, and a great public debate arose about the safety of flight and the Roma‘s reliance on hydrogen.

Although there were photographs, there were no newsreel cameras on hand to capture the moment the Roma exploded. Dazed survivors and shaken witnesses told their stories to the press, but there was no on-the-spot radio coverage to bring the death and destruction into listener’s homes. Newspapers covered the story for a few weeks, but eventually the Roma slipped to the back pages, then out of the news altogether. In time, the Roma disaster faded from America’s consciousness.

There are few reminders of the disaster today. Langley, now a major Air Force base, still refers to a parking lot where the Roma‘s hangar stood as the ”LTA area,” an acronym for ”lighter than air.’ Roma Road runs nearby.

At Norfolk International Terminals, the commercial port of Norfolk, not far from the site of the crash, stands a small monument, its perfunctory inscription telling little of the Roma and its fate, and nothing of the lives lost aboard it.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hindenburg_disaster

Hindenberg Airship disaster

http://www.astro.com/astro-databank/Accident:_Hindenburg

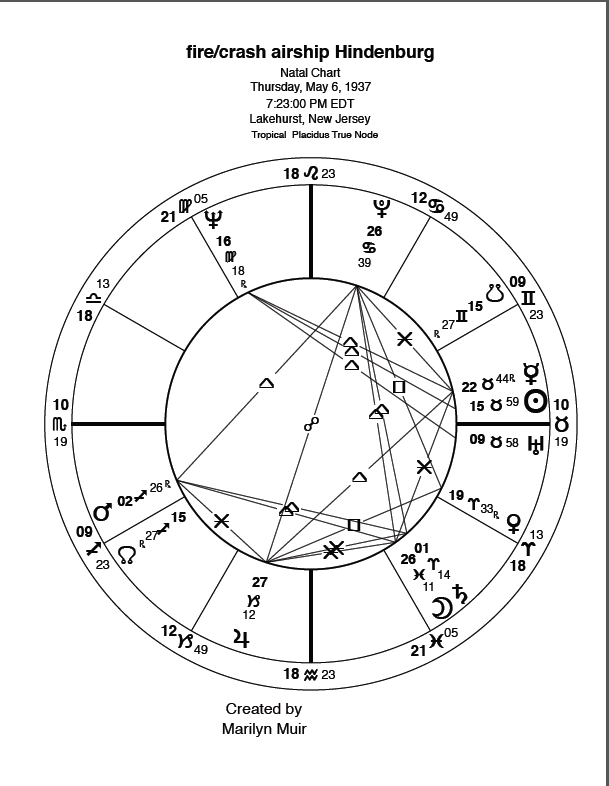

May 6, 1937 at 19:23 PM EDT

Lakehurst, NJ 40N00, 74W18

Rodden A, source New York Times

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hindenburg_disaster

Flight[edit]

After opening its 1937 season by completing a single round trip passage to Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, in late March 1937, the Hindenburg departed from Frankfurt, Germany, on the evening of May 3, 1937, on the first of 10 round trips between Europe and the United States that were scheduled for its second year of commercial service. The American Airlines company which had contracted with the operators of the Hindenburg was prepared to shuttle the fliers from Lakehurst to Newark for connections to airplane flights.[2]

Except for strong headwinds that slowed its progress, the crossing of the Hindenburg was otherwise unremarkable until the airship attempted an early evening landing at Lakehurst three days later on May 6. Although carrying only half its full capacity of passengers (36 of 70) and 61 crewmen (including 21 crewman trainees), the Hindenburg’s return flight was fully booked with many of those passengers planning to attend the festivities for the coronation of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth in London the following week.

The airship was hours behind schedule when she passed over Boston on the morning of May 6, and her landing at Lakehurst was expected to be further delayed because of afternoon thunderstorms. Advised of the poor weather conditions at Lakehurst, Captain Max Pruss charted a course over Manhattan Island, causing a public spectacle as people rushed out into the street to catch sight of the airship. After passing over the field at 4 p.m., Captain Pruss took passengers on a tour over the seasides of New Jersey while waiting for the weather to clear. After finally being notified at 6:22 p.m. that the storms had passed, the airship headed back to Lakehurst to make its landing almost half a day late. However, as this would leave much less time than anticipated to service and prepare the airship for its scheduled departure back to Europe, the public was informed that they would not be permitted at the mooring location or be able to visit aboard the Hindenburg during its stay in port.

Landing timeline[edit]

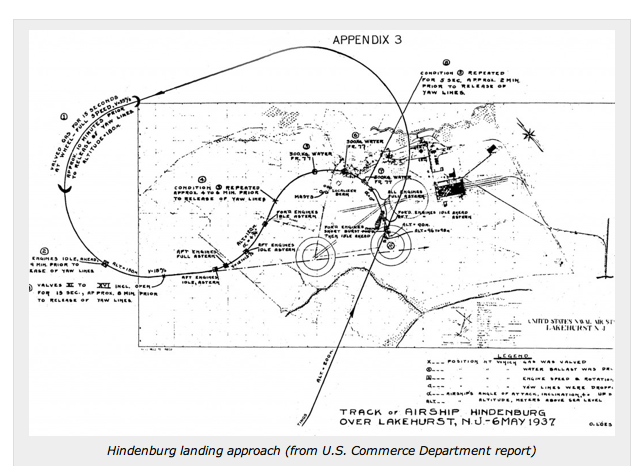

Around 7 p.m. local daylight saving time, at an altitude of 650 feet (200 m), the Hindenburg approached the Lakehurst Naval Air Station. This was to be a high landing, known as a flying moor, because the airship would drop its landing ropes and mooring cable at a high altitude, and then be winched down to the mooring mast. This type of landing maneuver would reduce the number of ground crewmen, but would require more time.

At 7:09 the airship made a sharp full speed left turn to the west around the landing field because the ground crew was not ready. At 11 minutes past, it turned back toward the landing field and valved gas. All engines idled ahead and the airship began to slow. Captain Pruss ordered all engines full astern at 7:14 while at an altitude of 394 ft (120 m), to try to brake the airship.

7:17: The wind shifted direction to southwest, and Captain Pruss ordered a second sharp turn towards starboard

7:18: As the final turn progressed, Pruss ordered 300, 300, and 500 kg of water ballast in successive drops because the airship was stern-heavy. Six men (four of whom were killed in the accident)[N 1] were also sent to the bow to trim the airship.

7:21: At altitude 295 feet (90 m), the mooring lines were dropped from the bow, the starboard line being dropped first, followed by the port line. The port line was overtightened as it was connected to the post of the ground winch. The starboard line had still not been connected. A light rain began to fall as the ground crew grabbed the mooring lines.

At 7:25 p.m., a few witnesses saw the fabric ahead of the upper fin flutter as if gas were leaking.[3] Witnesses also reported seeing blue discharges — possibly static electricity, or St Elmo’s Fire — moments before the fire on top and in the back of the ship near the point where the flames first appeared.[4] Several other eyewitness testimonies suggest that the first flame appeared on the port side just ahead of the port fin, and was followed by flames which burned on top. Commander Rosendahl testified to the flames being “mushroom-shaped”. One witness on the starboard side reported a fire beginning lower and behind the rudder on that side. On board, people heard a muffled explosion and those in the front of the ship felt a shock as the port trail rope overtightened; the officers in the control car initially thought the shock was due to a broken rope.

Disaster[edit]

At 7:25 p.m local time, the Hindenburg caught fire and quickly became engulfed in flames.[3] Where the fire started is unknown; several witnesses on the port side saw yellow-red flames first jump forward of the top fin.

[3] Other witnesses on the port side noted the fire actually began just ahead of the horizontal port fin, only then followed by flames in front of the upper fin. One, with views of the starboard side, saw flames beginning lower and farther aft, near cell 1. No. 2 Helmsman Helmut Lau also testified seeing the flames spreading from cell 4 into starboard. Although there were five newsreel cameramen and at least one spectator known to be filming the landing, no camera was rolling when the fire started.

Wherever they started, the flames quickly spread forward. Instantly, a water tank and a fuel tank burst out of the hull due to the shock of the blast. This shock also caused a crack behind the passenger decks, and the rear of the structure imploded. Buoyancy was lost on the stern of the ship, and the bow lurched upwards while the ship’s back broke; the falling stern stayed in trim.

As the tail of the Hindenburg crashed into the ground, a burst of flame came out of the nose, killing nine of the 12 crew members in the bow. There was still gas in the bow section of the ship, so it continued to point upward as the stern collapsed down. The crack behind the passenger decks collapsed inward, causing the gas cell to explode. The scarlet lettering “Hindenburg” was erased by flames while the airship’s bow descended. The airship’s gondola wheel touched the ground, causing the bow to bounce up slightly as one final gas cell burned away. At this point, most of the fabric on the hull had also burned away and the bow finally crashed to the ground. Although the hydrogen had finished burning, the Hindenburg’s diesel fuel burned for several more hours. The time that it took for the airship to be destroyed has been disputed. Some observers believed that it took 34 seconds, others said that it took 32 or 37 seconds. Since none of the newsreel cameras were filming the airship when the fire started, the time of the start can only be estimated from various eyewitness accounts. One careful analysis of the flame spread by Addison Bain of NASA gives the flame front spread rate across the fabric skin as about 49 ft/s (15 m/s), which would have resulted in a total destruction time of about 16 seconds (245m / 15 m/s=16.3 s). Some of the duralumin framework of the airship was salvaged and shipped back to Germany, where it was recycled and used in the construction of military aircraft for the Luftwaffe. So were the frames of the LZ 127 Graf Zeppelin and LZ 130 Graf Zeppelin II when both were scrapped in 1940.[5]

Airship Disasters

Airships.net: A Dirigible and Zeppelin History Site

The Graf Zeppelin, Hindenburg, U.S. Navy Airships, and other Dirigibles

Hydrogen Airship Disasters

Dozens of hydrogen airships exploded or burned in the years before the Hindenburg disaster finally convinced the world that hydrogen is not an acceptable lifting-gas for airships carrying people. The following is a partial list of hydrogen-inflated airships that were destroyed by fire from accidental causes (the list does not include ships shot down in combat operations):

- LZ-4 (August 5, 1908)

- LZ-6 (September 14, 1910)

- LZ-12/Z-III (June 17, 1912)

- LZ-10 Schwaben (June 28, 1912)

- Akron (July 2, 1912)

- LZ-18/L-2 (October 17, 1913)

- LZ-30/Z-XI (May 20, 1915)

- LZ-40/L-10 (September 3, 1915)

- SL-6 (November 10, 1915)

- LZ-52/L-18 (November 17, 1915)

- LZ-31/L-6 and LZ-36/L-9 (September 16, 1916)

- LZ-53/L-17 and LZ-69/L-24 (December 28, 1916)

- SL-9 (March 30, 1917)

- LZ-102/L-57 (October 7, 1917)

- LZ-87/LZ-117, LZ-94/L-46, LZ-97/L-51, and LZ-105/L-58 (January 5, 1918)

- LZ-104/L-59 (April 7, 1918)

- Wingfoot Air Express (July 21, 1919)

- R-38/ZR-II (August 23, 1921)

- Roma (February 21, 1922)

- Dixmude (December 21, 1923)

- R101 (October 5, 1930)

- LZ-129 Hindenburg (May 6, 1937)

Description of the Accidents

LZ-4 (August 5, 1908)

After an emergency landing near Echterdingen, Germany, LZ-4 was was torn from its temporary mooring by a gust of wind and ignited after hitting a stand of trees.

Burned wreckage of LZ-4 near Echterdingen

LZ-6 (September 14, 1910)

LZ-6, owned by the world’s first passenger airline, DELAG, was destroyed at Baden-Oos by a hydrogen fire which began when a mechanic used petrol to clean the ship’s gondola.

LZ-12/Z-III (June 17, 1912)

LZ-12 ignited and burned in its hangar at Friedrichshafen while being deflated.

LZ-10 Schwaben (June 28, 1912)

The passenger airship Schwaben was destroyed by fire at the airship field at Düsseldorf when its hydrogen was ignited by static electricity from the ship’s rubberized fabric gas cells.

Wreck of LZ-10 Schwaben at Düsseldorf

Akron (July 2, 1912)

Melvin Vaniman’s airship Akron exploded 15 minutes after departing Atlantic City, New Jersey, during an attempt to cross the Atlantic.

LZ-18/L-2 (October 17, 1913)

An in-flight engine fire ignited the ship’s hydrogen, killing all aboard.

LZ-30/Z-XI (May 20, 1915)

The ship broke away from its ground crew after being damaged during removal from its hangar; it crashed nearby and was destroyed when its hydrogen ignited.

LZ-40/L-10 (September 3, 1915)

L-10 was destroyed by a hydrogen fire during a thunderstorm near Cuxhaven as it was returning to its base at Nordholz. It is likely the ship rose in an updraft and released hydrogen which was ignited by the atmospheric conditions. All 19 members of the crew were killed.

SL-6 (November 10, 1915)

SL-6 exploded and burned on takeoff, killing all aboard.

LZ-52/L-18 (November 17, 1915)

The ship caught fire and was destroyed while being refilled with hydrogen at the zeppelin base at Tønder.

LZ-31/L-6 and LZ-36/L-9 (September 16, 1916)

Both ships were destroyed by fire in their hangar at Fuhlsbüttel when hydrogen was ignited during refilling operations.

LZ-53/L-17 and LZ-69/L-24 (December 28, 1916)

While L-24 was being returned to the shed it shared with L-17 at Tønder, a gust of wind lifted the ship into the roof of the shed; a light bulb ignited a hydrogen fire which destroyed both ships.

SL-9 (March 30, 1917)

SL-9 burned after being struck by lightning in flight over the Baltic, killing all 23 persons aboard.

LZ-102/L-57 (October 7, 1917)

L-57 burned in its shed at the airship base of Niedergörsdorf–Jüterbog after being damaged by high winds during docking operations.

LZ-87/LZ-117, LZ-94/L-46, LZ-97/L-51, and LZ-105/L-58 (January 5, 1918)

An explosion at the zeppelin base at Ahlhorn ignited the hydrogen of all four ships.

LZ-104/L-59 (April 7, 1918)

L-59 exploded in flight and crashed at sea near Malta, killing all 21 members of the crew. L-59 was the famous “Africa Ship” which proved the feasibility of intercontinental zeppelin travel by carrying 15 tons of cargo and 22 persons on a record-breaking 4,225 mile flight during a military relief mission to German East Africa in November, 1917.

Wingfoot Air Express (July 21, 1919)

Goodyear’s Wingfoot Air Express ignited in mid-air and crashed through the skylight of the Illinois Trust & Savings Building in Chicago, Illinois, killing three persons on the ship and ten bank employees and injuring another 27 people. All subsequent Goodyear airships were inflated with helium.

R-38/ZR-II (August 23, 1921)

The British-built R-38 (intended to serve as the United State Navy airship ZR-II) suffered in-flight structural failure over the city of Hull, England and crashed into the River Humber where it ignited, killing 44 of the 49 men aboard.

Roma (February 21, 1922)

The United States Army airship Roma (built by Umberto Nobile) ignited when it hit high-tension electrical wires near Langley Field at Hampton Roads, Virginia, killing 34 of the ship’s 45 crew members. After the Roma disaster the United States government decided never again to inflate an airship with hydrogen.

Dixmude (December 21, 1923)

The French-operated Dixmude was destroyed over the Mediterranean Sea near the coast of Sicily by a hydrogen explosion visible from miles away. Dixmude’s gas cells had apparently been contaminated with air, creating an explosive mixture, and the ship may have been lifted by updrafts in a thunderstorm, causing hydrogen to be vented and then ignited by the electrically charged atmosphere.

R101 (October 5, 1930)

The poorly-designed British R101 lost altitude and sank into a hillside near Beauvais, France. The impact was slight and caused few if any injuries, but the ship’s hydrogen ignited and the ensuing inferno killed 48 of the 55 passengers and crew.

Wreckage of R101

LZ-129 Hindenburg (May 6, 1937)

Hindenburg was destroyed by a hydrogen fire at the Lakehurst Naval Air Station.

Hindenburg Burning at Lakehurst, New Jersey

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Airship

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_airship_accidents

1900s

- 2 May 1902: Semi-rigid airship Pax explodes over Paris, killing both crewmen.

- 13 October 1902: Separation of gondola from envelope over Paris kills two on board the Bradsky.

- 30 November 1907: Loss of the French Army’s Patrie – no fatalities.

- 23 May 1908: Morrell airship falls over Berkeley, California. All 16 survive but some with serious injuries.

- 4 August 1908: Zeppelin LZ 4 caught fire near Echterdingen after it broke loose from mooring and was blown into some trees..

- 25 September 1909: French Army’s La République crashes near Avrilly, Allier killing four.

1910s

- 13 July 1910: Airship Erbslöh explodes over Rhenish Prussia killing all five.

- 15 October 1910: American non-rigid airship America disappeared without a trace off Nova Scotia after being abandoned by its crew.

- 24 September 1911: HMA No. 1, more commonly known as the Mayfly was the first rigid airship to be built in the UK. It broke in two due to strong winds while being removed from her shed in Barrow-in-Furness for ground trials.

- 2 July 1912: Private airship Akron explodes on transatlantic attempt off Atlantic City killing all five, including inventor Melvin Vaniman.

- 4 September 1912: Budapest, Hungary. Military Airship, three soldiers killed while engaged in military training manoeuvres. The airship was being prepared for an ascent and was being held down by more than 100 soldiers, a heavy wind prevailed and a sudden gust carried the airship away. It arose rapidly and all but three of the men released their grip on the rope. These held on until exhaustion weakened their grip, causing them to fall to their deaths one by one.

- 9 September 1913: Imperial German Navy L 1 (Zeppelin LZ 14) crashed in a storm. 14 drowned, 6 survivors. First fatal Zeppelin accident.

- 17 October 1913: Imperial German Navy L 2 (Zeppelin LZ 18) caught fire and was destroyed during a test flight. All 28 killed.

- 20 June 1914: Austro-Hungarian Army Militärluftschiff III, destroyed in a collision with an army Farman HF.20 over Fischamend. All seven on airship killed along with the two in the biplane.

- 3 September 1915: Imperial German Navy L 10 (Zeppelin LZ 40) destroyed by fire on 3 September 1915 after being struck by lightning near Cuxhaven, killing 19 crew members.

- 10 November 1915: Imperial German Navy D.1 (Schütte-Lanz SL6) explodes after take-off over Seddin, killing all 20.

- 17 November 1915: Imperial German Navy L 18 (Zeppelin LZ 52) destroyed in shed fire at Tondern.

- 1 February 1916: Imperial German Navy L 19 (Zeppelin LZ 54) comes down in the North Sea, off the coast of the Netherlands, after an air-raid on the United Kingdom. All 16 crew survive the crash, but subsequently perish after the crew of a British fishing boat refuse to rescue them.

- 21 February 1916: In an experiment to launch a BE.2C fighter from under a SS-class non-rigid airship, Neville Usborne and another British officer are killed.[1]

- 12 May 1916: French airship CM-T-1 destroyed by fire near Porto Torres, Sardinia while en route to Fréjus/St Raphaël, France.

- 16 September 1916: Imperial German Navy L 6 (Zeppelin LZ 31) caught fire during inflation in hangar at Fuhlsbuttel and destroyed along with L 9 (Zeppelin LZ 36).

- 7 November 1916: Imperial German Army LZ 90 (Zeppelin LZ 60) disappeared without a trace after it broke loose in a storm and blown out to sea.

- 12 December 1917: North Sea class blimp N.S.5 sets off for RNAS East Fortune, but both engines fail within sight of her destination, and she drifts with the wind for about 10 miles (16 km) before they can be restarted. However, since both engines continue to be troublesome it is decided to make a “free balloon” landing, but the ship is damaged beyond repair during the attempt.

- 5 January 1918: Ahlhorn hangars explode destroying the LZ 87 (L 47), LZ 94 (L 46), LZ 97 (L 51), LZ 105 (L 58), and SL20. Fifteen killed, 134 injured.

- 7 April 1918: Imperial German Navy L 59 (Zeppelin LZ 104) explodes over Malta for reasons unknown, killing 21.

- 2 July 1919: US Navy blimp C-8 explodes while landing at Camp Holabird, Maryland, injuring ~80 adults and children who were watching it. Windows in homes a mile away are shattered by the blast.[2][3]

- 15 July 1919: Royal Navy North Sea class airship N.S.11 burns over the North Sea off Norfolk, England, killing twelve.[4][5] In the early hours of 15 July on what was officially supposed to be a mine-hunting patrol, she was seen to fly beneath a long “greasy black cloud” off Cley next the Sea on the Norfolk coast and a massive explosion was heard shortly after. A vivid glare lasted for a few minutes as the burning airship descended, and finally plunged into the sea after a second explosion. There were no survivors, and the findings of the official Court of Enquiry were inconclusive, but amongst other possibilities it was thought that a lightning strike may have caused the explosion.[6]

- 21 July 1919: American airship Wingfoot Air Express caught fire over downtown Chicago, 2 passengers, one crewmember and 10 people on the ground killed, 2 parachuted to safety.[7]

1920s

- 19 June 1920: US Navy Goodyear airship D-1, A4450, is destroyed by fire [8] at the Goodyear Wingfoot Lake Airship Base, Suffield Township, Portage County, Ohio.[9]

- 7 July 1921: US Navy airship C-3 burned at Naval Air Station Hampton Roads, Norfolk, Virginia[10]

- 23 August 1921: British R38. Built for US Navy and already carrying “ZR-2” markings, broke in half and burned after suffering structural failure during high-speed trials over Hull. 44 killed, 5 survivors.

- 31 August 1921: US Navy airship D-6, A5972, burned in hangar fire at NAS Rockaway along with airships C-10 and H-1 and kite balloon A-P.

- 21 February 1922: US Army airship Roma (ex-Italian T34). Hit power lines in Virginia and caught fire. 34 killed, 11 survivors.

- 17 October 1922: U.S. Army’s largest blimp, C-2 (A4419), catches fire shortly after being removed from its hangar at Brooks Field, San Antonio, Texas for a flight. Seven of eight crew aboard are injured, mostly in jumping from the craft. This accident was made the occasion for official announcement by the Army and the Navy that the use of hydrogen would be abandoned “as speedily as possible.”[11] On 14 September 1922, the C-2 had made the first transcontinental airship flight, from Langley Field, Virginia, to Foss Field, California, under the command of Maj. H. A. Strauss.[12]

- 21 December 1923: French Navy’s Dixmude (ex Zeppelin LZ114). Struck by lightning over Mediterranean near Sicily and explodes in mid-air. All 50 aboard killed.[13]

- 10 October 1924: US Army blimp TC-2 explodes over Newport News when a bomb it was carrying detonates. Two of the crew of five were killed.

- 3 September 1925: US Navy USS Shenandoah (ZR-1). Caught in storm over Noble County, Ohio, and broke into several pieces. 14 killed, 29 survivors.

- 25 May 1928: Italian semi-rigid Italia. Crashed on return from successful trip to North Pole. 7 killed, 1 crash survivor died from exposure, 8 rescued, 6 rescuers lost including Roald Amundsen.

1930s

- 5 October 1930: British experimental design R101. Dove into ground during rainstorm in France. 48 killed, 6 survivors.[14] This is the deadliest civilian airship accident.

- 11 May 1932: Abortive landing of USS Akron – ropes pull three members of the mooring crew high into the air; two fall to their deaths, the third is saved.

- 4 April 1933: USS Akron. Lost at sea off coast of New Jersey in severe storm due to instrument error[citation needed]. With 73 dead – many drowned – and 3 survivors, this is the deadliest airship accident.

- 4 April 1933: US Navy airship J-3 A7382 lost in surf off New Jersey coast with two crew killed while looking for USS Akron survivors.

- 16 August 1934: Soviet SSSR-V7 Chelyushinets burned in its hangar at Dolgoprudny along with the V4 and V5; the fire was caused by a lightning strike.

- 12 February 1935: USS Macon crashed off coast of Point Sur, Monterey, California after crosswinds broke an already damaged section. 2 dead, 81 survivors.

- 24 October 1935: Soviet SSSR-V7 bis hit a powerline near the Finnish border causing a fire, one crew member died while the rest managed to escape.

- 6 May 1937: German Hindenburg burned on landing at Lakehurst, New Jersey. 35 dead, 1 on ground killed, 62 survivors.

- 6 February 1938: Soviet SSSR-V6 OSOAVIAKhIM – 13 out of 19 crew died after crashing into a mountain some 300 km south of Murmansk on a practice flight for an arctic rescue mission.

- 6 August 1938: Soviet SSSR-V10 crashed near Beskudnikovo killing all seven crew.

1940s

- 8 June 1942: U.S. Navy blimps G-1 and L-2 collide mid-air, killing twelve including five civilian scientists.

- 16 August 1942: Designated Flight 101. The two experienced crew of the U.S. Navy blimp L-8 disappeared without explanation during the flight giving it the name “The Ghost Blimp.” The blimp drifted inland from its Pacific patrol route, striking the ground and leaving its depth charge armament on the beach. It then lifted off and drifted further inland and crashed on a downtown street in Daly City, California. The gondola door had been latched open, and the safety bar which was normally used to block the doorway was no longer in place. Two of the three life jackets on board were missing, but these would have been worn by the two crew during flight, as regulations required. A year after their disappearance the pilots were officially declared dead.[15]

- 19 April 1944: U.S. Navy airship K-133, of Airship Patrol Squadron 22 (ZP-22), operating out of NAS Houma, Louisiana, was caught in a thunderstorm while patrolling over the Gulf of Mexico. It went down and twelve of thirteen crew were lost; the sole survivor was recovered after spending 21 hours in the water.[16]

- 21 April 1944: The southeast door of blimp hangar at NAS Houma, Louisiana, was chained open due to a fault. A gust of wind carried three K-class blimps, all of ZP-22, out into the night. K-56 traveled 4.5 miles[clarification needed] before crashing into trees. K-57, caught fire 4 miles[clarification needed] from the air station. K-62, fetched up against high-tension powerlines a quarter mile away and burned. K-56 was salvaged, repaired at Goodyear at Akron, Ohio, repaired and returned to service.[16][17]

- 16 May 1944: Training accident at Lakehurst, New Jersey kills ten of eleven crewmen of K-5 as it crashes into the number one hangar.

- 2 July 1944: U.S. Navy blimp K-14 crashes off Maine, killing six of the ten crewmen. Her loss has been attributed to accident or machine gun fire from a U-boat.

- 7 July 1944: U.S. Navy blimp K-53 falls into the Caribbean, killing one of her crew of ten.

- 17 October 1944: U.S. Navy blimp K-111 crashes on Santa Catalina Island, California, killing six of her ten crewmen.

- 5 November 1944: U.S. Navy blimp K-34 crashes off the coast of the State of Georgia, killing two of eleven crewmen.

- 3 May 1945: A Navy blimp’s fuel tanks explodes over Santa Ana, California killing eight of nine.

- 29 January 1947: Soviet airship Pobeda gets caught in a powerline and crashes killing all three on board.

1950s

- 14 May 1959: US Navy ZPG-2 crashes into hangar roof during a dense fog at Lakehurst, New Jersey killing one and injuring 17.

1960s

- 6 July 1960: US Navy ZPG-3W crashed into the sea off New Jersey. 18 of the 21 crew were killed.

1980s

- 8 October 1980: The 170-foot EA-1 Jordache blimp, N5499A, leased by Jordache Enterprises Co., crashes at Naval Air Engineering Station Lakehurst, New Jersey on its maiden flight. With an 0815 hrs. launch, and a flightplan to Teterboro Airport and thence to a Manhattan photo shoot, the airship, weighed down with gold and burgundy paint, reached 600 feet altitude before beginning an unplanned right descending turn, with pilot James Buza, 40, making a “controlled descent” into a garbage dump, impaling the blimp on a pine tree, coming down just a quarter mile from the site of the Hindenburg‘s 1937 demise. Buza, the only crewmember, was unhurt.[18] According to the NTSB report, the cause was poor design. The pilot also had zero hours experience in the type.

- 1 July 1986: The experimental Helistat 97-34J crashes at Naval Air Engineering Station Lakehurst in Lakehurst, New Jersey during a test flight, killing one.

1990s

- 4 July 1993: US LTA 138S airship Bigfoot, which bore the Pizza Hut logo crashed on top of buildings in Manhattan. The cause included inadequate FAA standards according to the NTSB report.[19][20]

- May 1995: The Goodyear blimp GZ-20 Eagle, tail number N10A, suffered a deflationary incident, when the blimp struck the ground near the Carson, California, mooring site while unmanned. This blimp was repaired and rechristened as the Eagle N2A. No injuries were reported.

- 1 July 1998: Icarus Aircraft Inc. / American Blimp Corporation ABC-A-60, N760AB, encountered severe downdraft on positioning flight from Williamsport, Pennsylvania to Youngstown, Ohio, and was substantially damaged when it impacted trees at 1105 hrs. during uncontrolled descent ~eight miles (~13 km) NW of Piper Memorial, near Lock Haven, Pennsylvania. After being blown from treetop to treetop for about ten minutes, gondola settled in a tree about 40 feet (12 m) in the air and the two pilots exited uninjured and climbed down the tree. Some fifteen minutes later the airship was blown another 900 feet (275 m) before coming to rest.[21]

- 28 October 1999: The Goodyear blimp GZ-22 “Spirit of Akron”, N4A, crashed in Suffield Township, Ohio, when it suddenly entered an uncontrolled left turn and began descending. The pilot and technician on board received only minor injuries when the blimp impacted with trees. The NTSB reported the probable cause as being improperly hardened metal splines on the control actuators shearing and causing loss of control.[22]

2000s

- 16 June 2005: A model GZ-20 Goodyear blimp named Stars and Stripes (N1A), crashed shortly after take off in Coral Springs, Florida. No one was injured. Bad weather may have been a factor in the incident.

- 26 September 2006: The Hood blimp, an American Blimp Corporation A-60, crashed into a wooded area of Manchester-by-the-Sea, Massachusetts. The airship left Beverly Municipal Airport at about 1215 hrs. Shortly after, the pilot started to have problems, and he tried to land on Singing Beach, but instead got caught in some trees near Brookwood Road. The pilot was not injured.

2010s

- 14 June 2011: A Goodyear Blimp operated by The Lightship Group in Reichelsheim (Wetterau), Germany caught fire and crashed, resulting in the death of Michael Nerandzic, an experienced pilot whose last-minute actions saved the lives of his three passengers.[23]

- 14 August 2011: the Hangar-1 blimp operated by The Lightship Group broke free of its mooring in Worthington, Ohio, crash landing in a yard. No injuries.[24]

- 4 May 2012: An Israeli spy blimp crashed when a crop duster struck the blimp’s side.[25]

References will not load – all list “Jump Up”. Use newest webpage listings for source notes.

- Jump up

- ^ H. J. C Harper “Composite History” Flight 1 November 1937

- Jump up

- ^ http://www.hsobc.org/Documents/BC%20Timeline.pdf

- Jump up

- ^ The New York times index – Google Books. Books.google.com. Retrieved 2010-11-25.

- Jump up

- ^ The New York Times, July 16, 1919, Wednesday, Page 1, British Airship Burns with Crew; Twelve Lost When the NS-11 Falls Flaming Into the North Sea.

- Jump up

- ^ The New York Times, July 27, 1919, Sunday, Editorial, Page 39, Helium for Flying; Noninflammable Gas May Yet Be Produced in Quantities and at a Cost Suited for Dirigibles.

- Jump up

- ^ Loss of N.S.11. Warmsley, N. Retrieved on 5 April 2009.

- Jump up

- ^ “Chicago Public Library Archive”. Retrieved 16 November 2014.

- Jump up

- ^ Swanborough, Gordon, and Bowers, Peter M., “United States Navy Aircraft since 1911”, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Maryland, 1976, Library of Congress card number 90-60097, ISBN 0-87021-792-5, pages 573–574.

- Jump up

- ^ “A Brief History of the Wingfoot Lake Airship Base”. Goodyearblimp.com. Retrieved 2010-11-25.

- Jump up

- ^ The New York Times, July 8, 1921, Friday, Page 1, Big Navy Dirigible Burned in Flight; Flames Destroy the C-3 at Hampton Roads

- Jump up

- ^ Roseberry, C. R., “The Challenging Skies – The Colorful Story of Aviation’s Most Exciting Years, 1919–1939”, Doubleday & Company, Inc., Garden City, New York, 1966, Library of Congress card number 66-20929, page 347.

- Jump up

- ^ “Official Site of the U.S. Air Force – History Milestones”. Retrieved 16 November 2014.

- Jump up

- ^ “Avalanche Press”. Retrieved 16 November 2014.

- Jump up

- ^ *Report of the R101 Inquiry 1931 HMSO p.7

- Jump up

- ^ Check Six (May 2008). “The Crash of Navy Blimp L-8”. Retrieved 2008-11-17.

- ^ Jump up to:

- a b Shettle, M. L., “United States Naval Air Stations of World War II – Volume II : Western States“, Schaertel Publishing Co., Bowersville, Georgia, 1997, Library of Congress card number 96-070565, ISBN 0-9643388-1-5, page 99.

- Jump up

- ^ http://home.att.net/~jbaugher/thirdseries4.html

- Jump up

- ^ Associated Press, “Blimp Crashes Near Zeppelin Crash Site”, Anderson Independent, Anderson, South Carolina, Thursday, October 9, 1980, page 4A.

- Jump up

- ^ NTSB Accident report File No. 1036 07/04/1993 NEW YORK, N832US

- Jump up

- ^ “New York Times”. 5 July 1993. Retrieved 16 November 2014.

- Jump up

- ^ “Airscene: Commercial Accidents”, AIR International, Stamford, Lincs, U.K., September 1998, Volume 55, Number 3, page 142.

- Jump up

- ^ NTSB Aviation Accident IAD00LA002

- Jump up

- ^ “Blimp pilot dies saving passengers from fiery crash”. CNN. June 14, 2011. Retrieved 2011-06-15.

- Jump up

- ^ http://www.washingtonpost.com/national/heavy-winds-lift-128-foot-long-blimp-moored-at-ohio-state-airport-into-air-hasnt-been-found/2011/08/14/gIQAnVSWEJ_story.html. Missing or empty |title= (help)[dead link]

- Jump up ^ “Israeli spy blimp crashes near Gaza”. The Aviationist. May 6, 2012. Retrieved 2012-07-28.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Accidents_and_incidents_involving_balloons_and_airships

List of airship accidents

A

- Airship Italia

- Airship N.S.11 crash

- USS Akron (ZRS-4)

- 1989 Alice Springs hot air balloon crash

- S. A. Andrée’s Arctic Balloon Expedition of 1897

C

- 2012 Carterton hot air balloon crash

D

- Adelir Antônio de Carli

- Dixmude (airship)

E

- Erbslöh

H

- Helgoland Island air disaster

- Hindenburg disaster

J

- Johannisthal air disaster

L

- La République (airship)

- 2012 Ljubljana Marshes hot air balloon crash

- 2013 Luxor hot air balloon crash

- LZ 54 (L 19)

R

- R38-class airship

- Roma (airship)

S

- USS Shenandoah (ZR-1)

- SSSR-V6 OSOAVIAKhIM

W

- Wingfoot Air Express crash

~

Template:Accidents and incidents involving hot air balloons

Hindenburg Disaster

The Hindenburg disaster at Lakehurst, New Jersey on May 6, 1937 brought an end to the age of the rigid airship.

The disaster killed 35 persons on the airship, and one member of the ground crew, but miraculously 62 of the 97 passengers and crew survived.

Almost 80 years of research and scientific tests support the same conclusion reached by the original German and American accident investigations in 1937: It seems clear that the Hindenburg disaster was caused by an electrostatic discharge (i.e., a spark) that ignited leaking hydrogen.

The spark was most likely caused by a difference in electric potential between the airship and the surrounding air: The airship was approximately 60 meters (about 200 feet) above the airfield in an electrically charged atmosphere, but the ship’s metal framework was grounded by its landing line; the difference in electric potential likely caused a spark to jump from the ship’s fabric covering (which had the ability to hold a charge) to the ship’s framework (which was grounded through the landing line). A somewhat less likely but still plausible theory attributes the spark to coronal discharge, more commonly known as St. Elmo’s Fire.

The cause of the hydrogen leak is more of a mystery, but we know the ship experienced a significant leakage of hydrogen before the disaster.

No evidence of sabotage was ever found, and no convincing theory of sabotaged has ever been advanced.

One thing is clear: the disaster had nothing to do with the zeppelin’s fabric covering. Hindenburg was just one of many hydrogen airships destroyed by fire because of their flammable lifting gas, and suggestions about the alleged flammability of the ship’s outer covering have been repeatedly debunked. The simple truth is that Hindenburg was destroyed in 32 seconds because it was inflated with hydrogen.

The Last Flight of the Hindenburg

Hindenburg began its last flight on May 3, 1937, carrying 36 passengers and 61 officers, crew members, and trainees. It was the airship’s 63rd flight.

The ship left the Frankfurt airfield at 7:16 PM and flew over Cologne, and then crossed the Netherlands before following the English Channel past the chalky cliffs of Beachy Head in southern England, and then heading out over the Atlantic shortly after 2:00 AM the next day.

Hindenburg followed a northern track across the ocean [view chart], passing the southern tip of Greenland and crossing the North American coast at Newfoundland. Headwinds delayed the airship’s passage across the Atlantic, and the Lakehurst arrival, which had been scheduled for 6:00 AM on May 6th, was postponed to 6:00 PM.

By noon on May 6th the ship had reached Boston, and by 3:00 PM Hindenburg was over the skyscrapers of Manhattan in New York City (view photograph).

The ship flew south from New York and arrived at the Naval Air Station at Lakehurst, New Jersey at around 4:15 PM, but the poor weather conditions at the field concerned the Hindenburg’s commander, Captain Max Pruss, and also Lakehurst’s commanding officer, Charles Rosendahl, who sent a message to the ship recommending a delay in landing until conditions improved. Captain Pruss departed the Lakehurst area and took his ship over the beaches and coast of New Jersey to wait out the storm. By 6:00 PM conditions had improved; at 6:12 Rosendahl sent Pruss a message relaying temperature, pressure, visibility, and winds which Rosendahl considered “suitable for landing.” At 6:22 Rosendahl radioed Pruss “Recommend landing now,” and at 7:08 Rosendahl sent a message to the ship strongly recommending the “earliest possible landing.”

The Landing Approach

Hindenburg approached the field at Lakehurst from the southwest shortly after 7:00 PM at an altitude of approximately 600 feet. Since the wind was from the east, after passing over the field to observe conditions on the ground, Captain Pruss initiated a wide left turn to fly a descending oval pattern around the north and west of the field, to line up for a landing into the wind to the east.

While Captain Pruss (who was directing the ship’s heading and engine power settings) brought Hindenburg around the field, First Officer Albert Sammt (who was responsible for the ship’s trim and altitude, assisted by Watch Officer Walter Ziegler at the gas board and Second Officer Heinrich Bauer at the ballast board), valved 15 seconds of hydrogen along the length of the ship to reduce Hindenburg’s buoyancy in preparation for landing.

While Captain Pruss (who was directing the ship’s heading and engine power settings) brought Hindenburg around the field, First Officer Albert Sammt (who was responsible for the ship’s trim and altitude, assisted by Watch Officer Walter Ziegler at the gas board and Second Officer Heinrich Bauer at the ballast board), valved 15 seconds of hydrogen along the length of the ship to reduce Hindenburg’s buoyancy in preparation for landing.

As Pruss continued the slow left turn of the oval landing pattern, reducing, and then reversing, the power from the engines, Sammt noticed that the ship was heavy in the tail and valved hydrogen from cells 11-16 (in the bow) for a total of 30 seconds, to reduce the buoyancy of the bow and keep the ship in level trim. When this failed to level the ship, Sammt ordered three drops of water ballast, totaling 1,100 kg (2,420lbs), from Ring 77 in the tail, and then valved an additional 5 seconds of hydrogen from the forward gas cells. When even these measures could not keep the ship in level trim, six crewmen were ordered to go forward to add their weight to the bow.

(That Captain Pruss personally directed the ship’s heading and power settings during the landing evolution was an exception to the usual German operating procedure. Typically, during the landing of Hindenburg or Graf Zeppelin, the rudder and power were under the direction of one senior watch officer, while the elevators, ballast, and gas were under the direction of another senior watch officer; the ship’s captain observed all operations, but only intervened in the case of difficulty or disagreement with the actions of his officers. The German procedure was noted frequently by American naval observers, perhaps because it differed so greatly from the practice followed by the United States Navy. During Hindenburg’s final landing maneuver, however, Captain Pruss personally directed the rudder and power, while Albert Sammt directed the elevators, ballast, and gas. Perhaps Pruss was simply used to this arrangement from his time as a watch officer, or perhaps a re-ordering of roles occurred because of the presence of senior captain and DZR flight director Ernst Lehmann on the bridge, but as far as this author knows, Captain Pruss never commented on the matter publicly, nor did Pruss ever try to evade his responsibility as commander by suggesting that Captain Lehmann was in actual operational control at the time of the accident.)

While Sammt was working to keep the ship in trim, the wind shifted direction from the east to the southwest. Captain Pruss now needed to land into the wind on a southwestly heading, rather than the easterly heading he had originally intended when he planned his oval landing pattern. Hindenburg was now close to the landing area, however, and did not have a lot of room to maneuver before reaching the mooring mast. Anxious to land quickly, before weather conditions could deteriorate, Captain Pruss decided to execute a tight S-turn to change the direction of the ship’s landing; Pruss ordered a turn to port to swing out, and then a sharp tight turn to starboard to line up for landing into the wind. (Some experts would later theorize that this sharp turn overstressed the ship, causing a bracing wire to snap and slash a gas cell, allowing hydrogen to mix with air to form a highly explosive combination.)

After the S-turn to change the direction of landing, Pruss continued his approach to the mooring mast, adjusting power from the two forward and two rear engines, and at 7:21, with the ship about 180 feet above the ground, the forward landing ropes were dropped.

The Fire

A few minutes after the landing lines were dropped, R.H. Ward, in charge of the port bow landing party, noticed what vhe described as a wave-like fluttering of the outer cover on the port side, between frames 62 and 77, which contained gas cell number 5 . He testified at the Commerce Department inquiry that it appeared to him as if gas were pushing against the cover, having escaped from a gas cell. Ground crew member R.W. Antrim, who was at the top of the mooring mast, also testified that he saw that the covering behind the rear port engine fluttering.

At 7:25 PM, the first visible external flames appeared. Reports vary, but most witnesses saw the first flames either at the top of the hull just forward of the vertical fin (near the ventilation shaft between cells 4 and 5) or between the rear port engine and the port fin (in the area of gas cells 4 and 5, where Ward and Antrim had seen the fluttering).

Did not load balance of article, many other articles on Google

The First Zeppelins LZ -1 thru 4

complete list of Zeppelins

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Zeppelins

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.