by Marilyn Muir, LPMAFA

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

In 2015, I found scattered material on the Tulsa Race Riot of which I had known nothing. As usual, I started collecting, researching, and trying to find and proof the resources. I got stuck on one particular report and never managed to actually finish or write the narrative. Fast forward to this week and here it is – the 100th anniversary of the tragedy. It was too late for me to develop the whole story astrologically. Chagrined at my not paying enough attention to the timing, I decided I would put all my Tulsa research material online in the Study Resources section of my website so all of you could have a chance to initiate your own research (one of the main reasons for the website) using my treasure trove of timed information. I will probably write an extensive narrative at some point, because I do have a boatload of charting for the tragedy, but this will take me some time and the history lesson is in the headlines now.

Included in this info are a huge number of charts, erected as I worked my way through the news sources, traveling where the story led me. Because the Greenwood area where the horror took place is within the city of Tulsa, which is in the state of Oklahoma, which in turn is in the USA, I studied the founding, the history and the legalities as those are parts of the larger picture. Greenwood was decimated, Tulsa was devastated, and the effect on Oklahoma and the U.S.A. was obfuscated and buried in misinformation. This needs to be remedied historically because lies and distortions do not make good contributions to history books. The story itself can be seen in the charts if you know how to look for it. What is included in this file is:

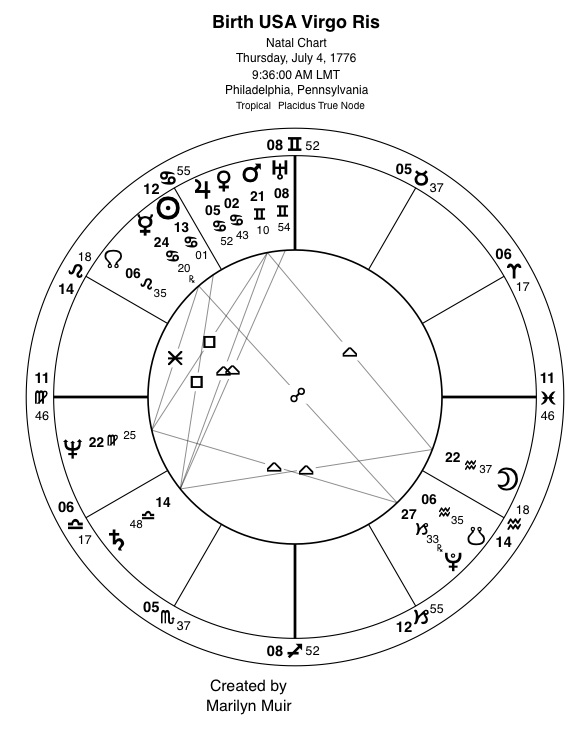

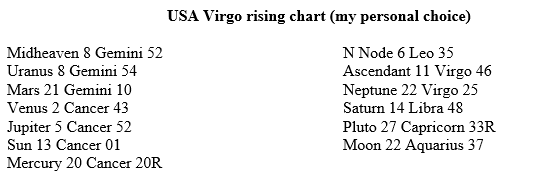

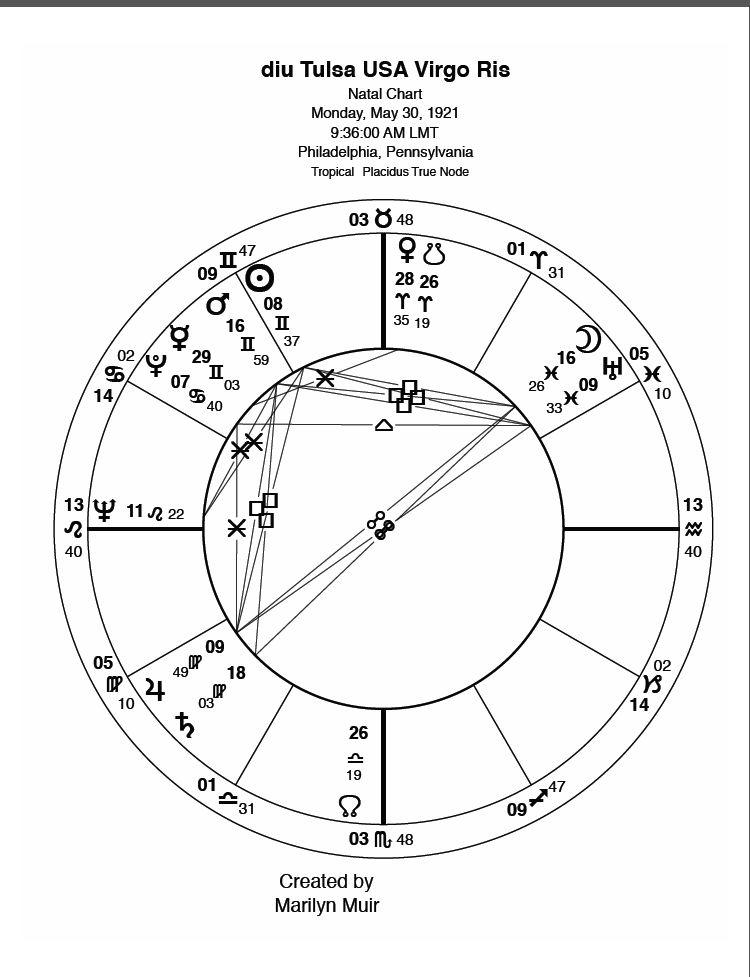

- The U.S. Declaration of Independence chart that I use (rectified by my own research) is July 4, 1776, 9:36 AM LMT, Philadelphia, PA. There are multiple choices, but this is my choice of charts.

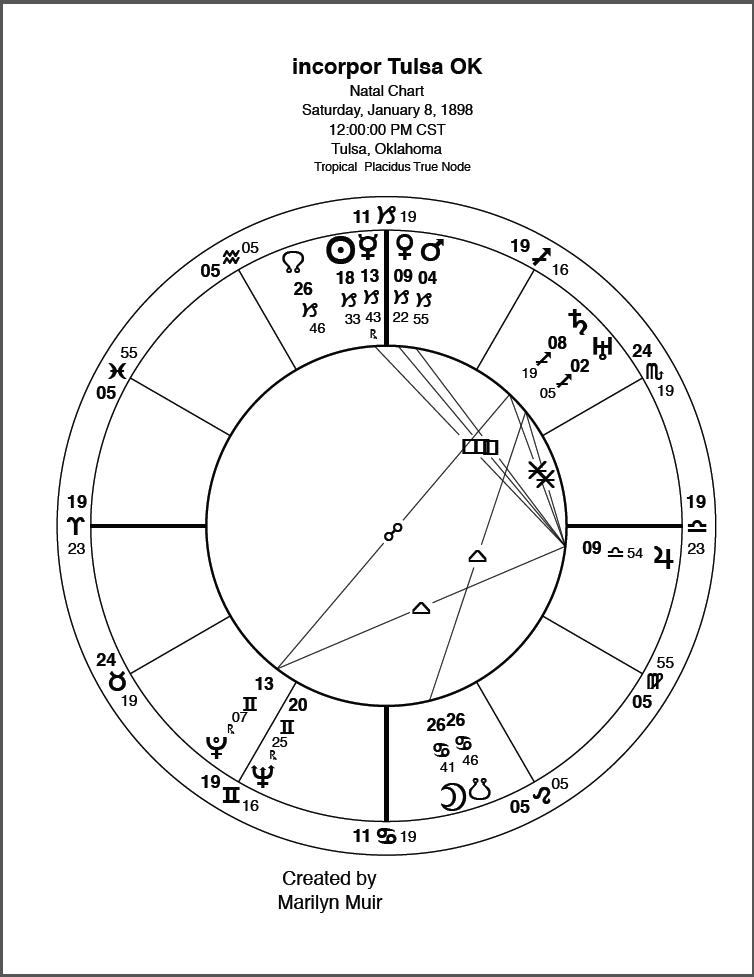

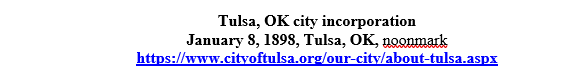

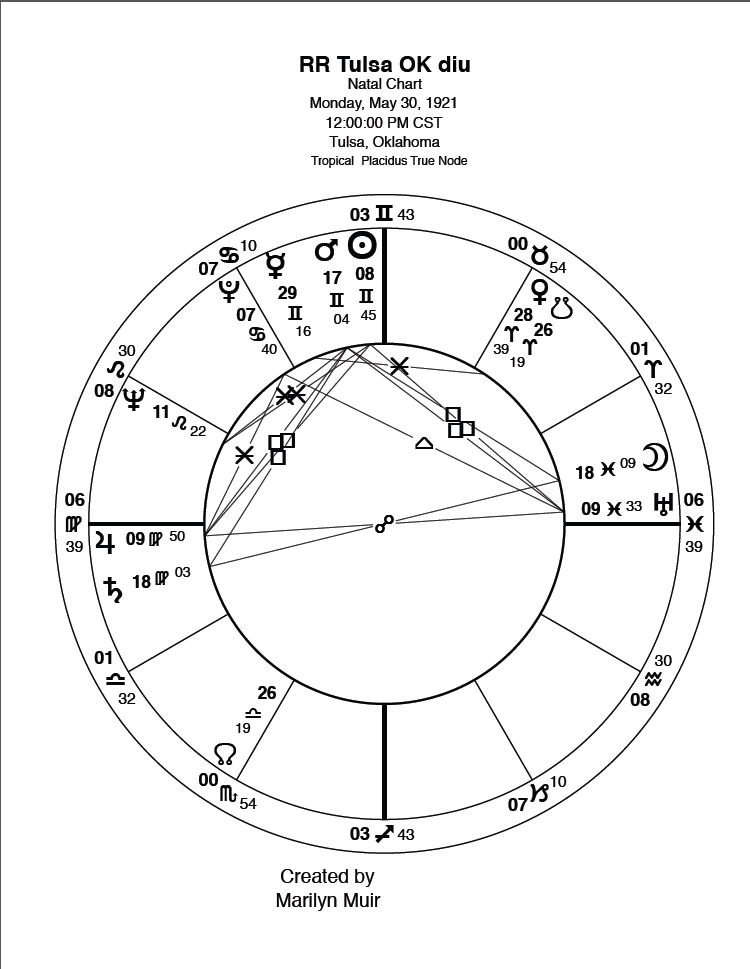

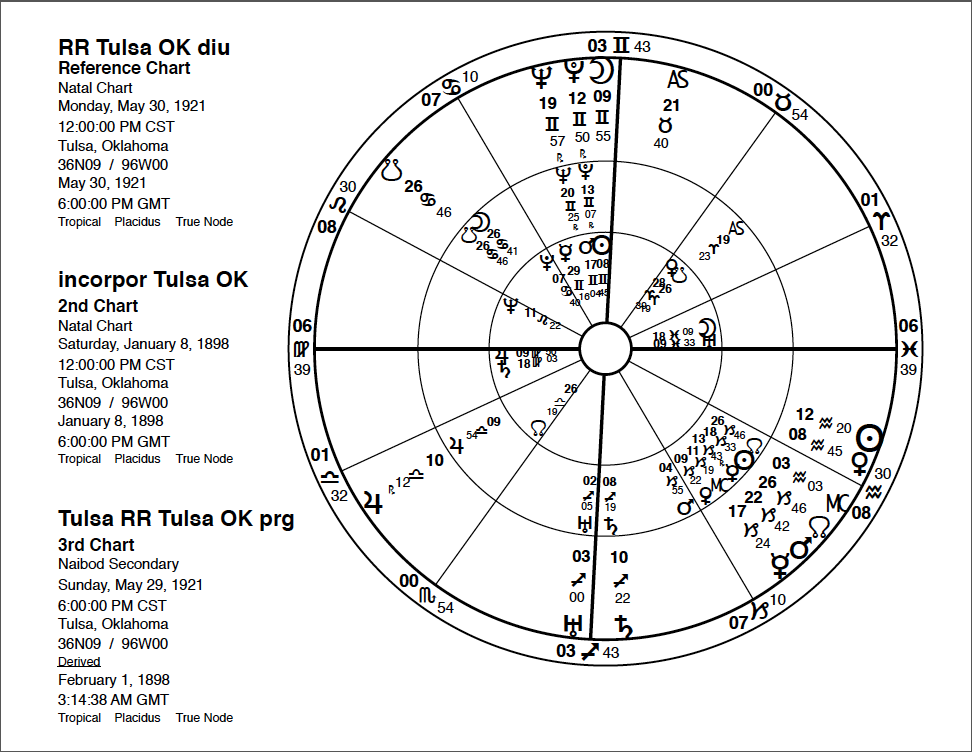

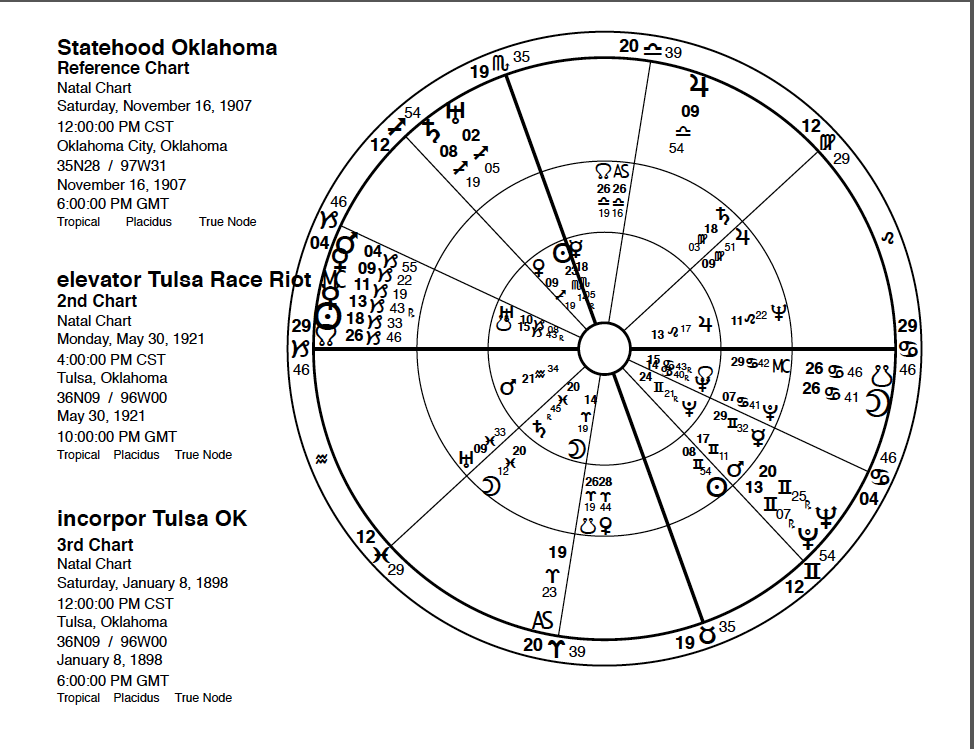

- Tulsa was an existing city before Oklahoma became a state, so this city chart is older than the state chart. That is true of several state capitals compared to their states. The best information I could access for Tulsa’s incorporation was Jan 8, 1898, noonmark used (typical business chart), with Tulsa as the location. Usual choices can be the city itself or the capital of the state in question. I usually prefer the location of the city because multiple municipal incorporations could be issued in a single session at the state offices and a specified location helps differentiate them. In this instance, statehood did not exist on the day of Tulsa’s incorporation.

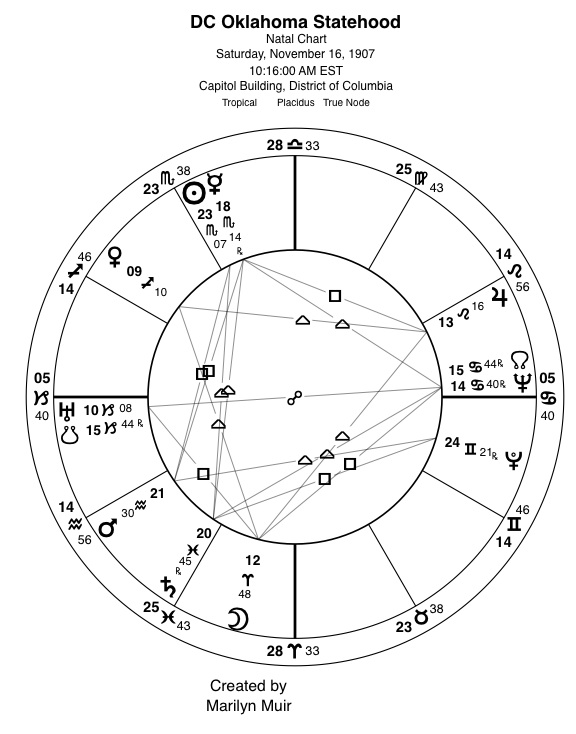

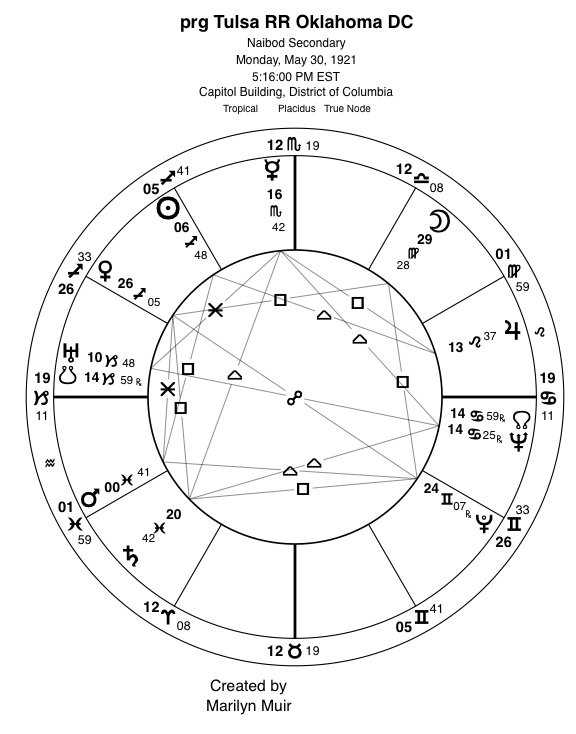

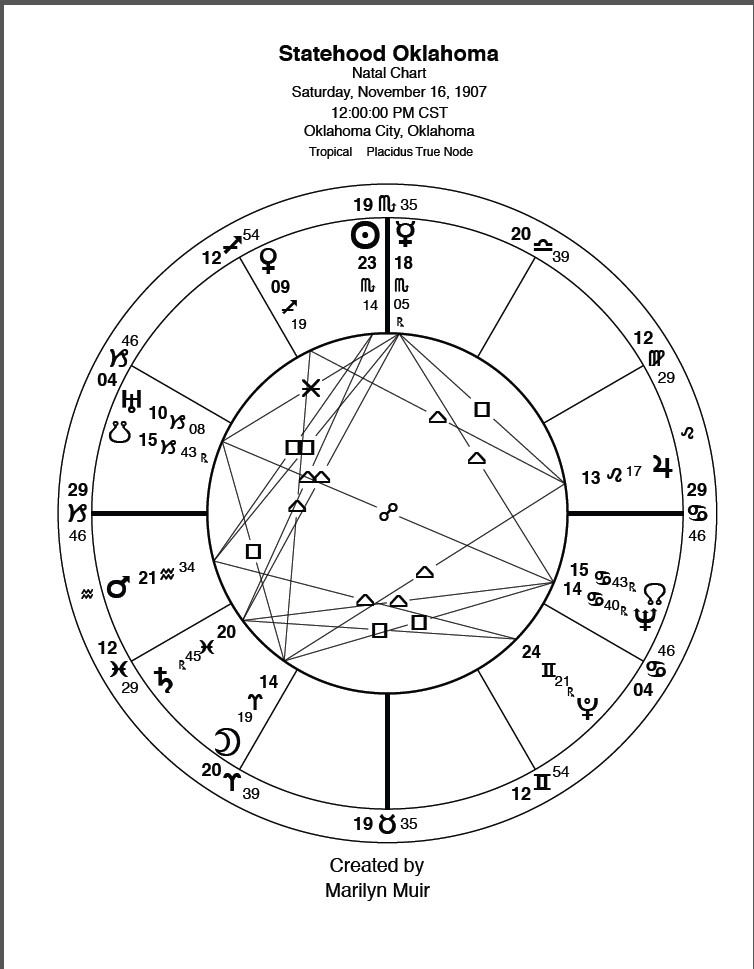

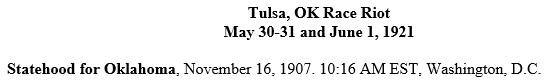

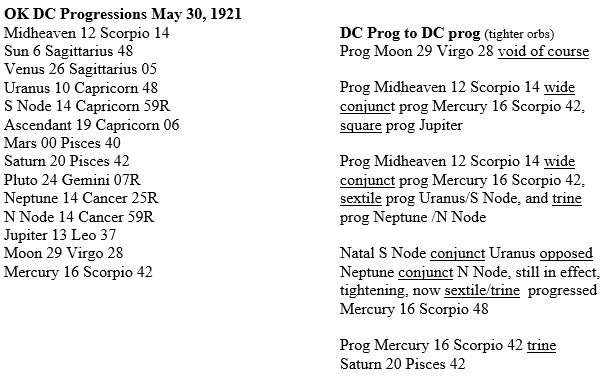

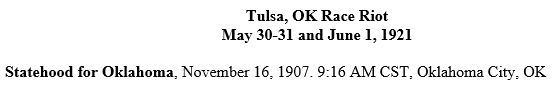

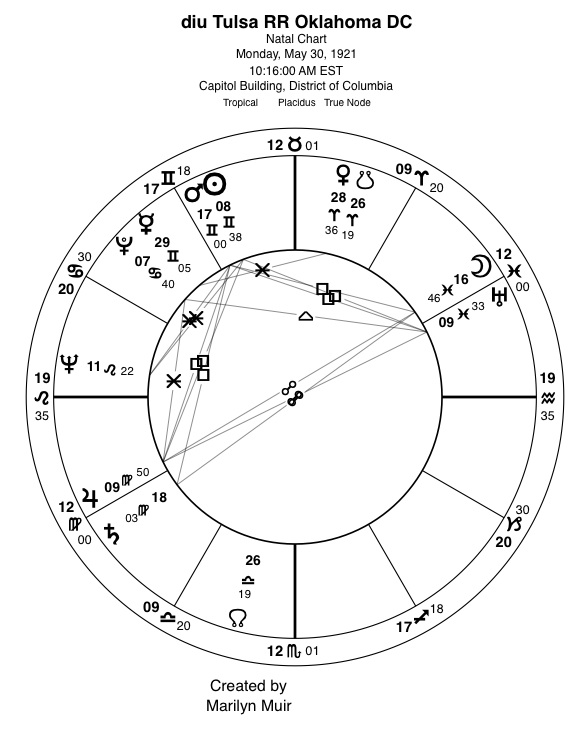

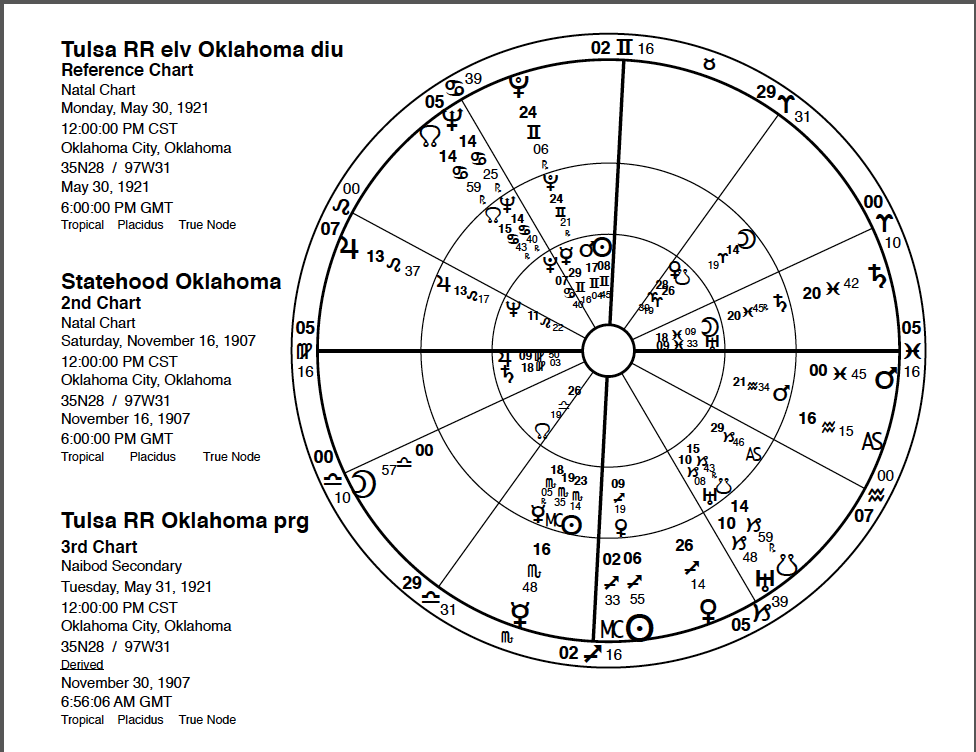

- Oklahoma statehood has two locations to consider. I have an article that states that President Theodore Roosevelt signed Oklahoma statehood November 16, 1907 at 8:16 AM EST at the Capitol Building, Washington, D.C. To have a timed state chart signing is rare.

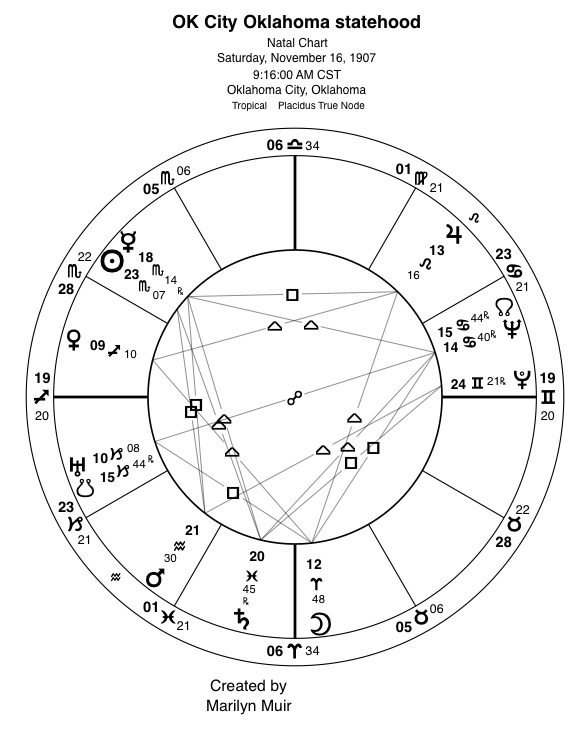

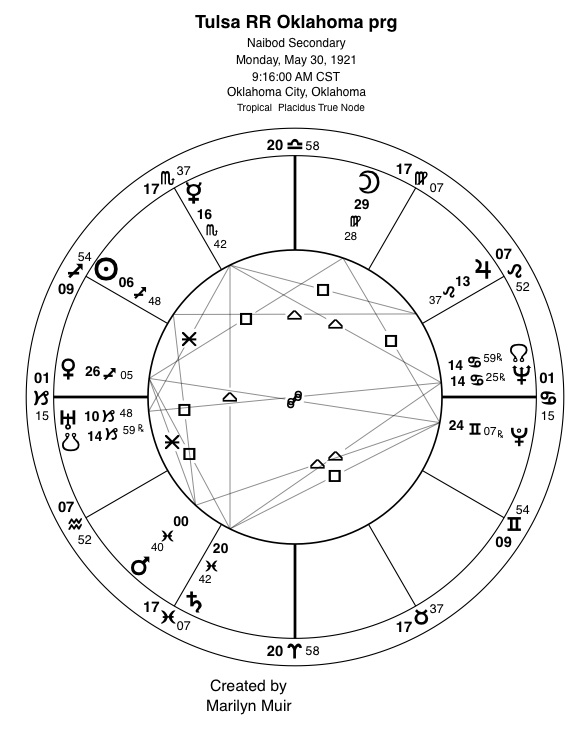

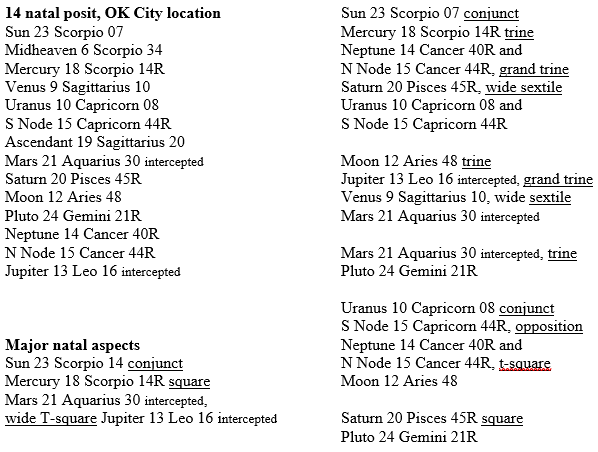

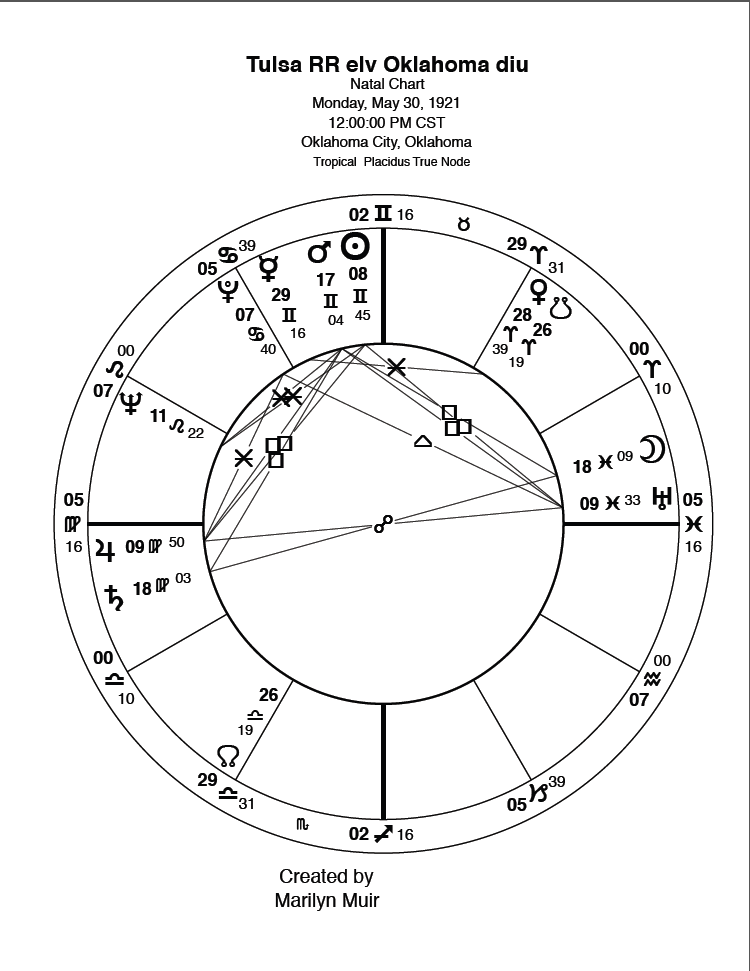

- The usual noonmark business chart for that date at the state capital: Oklahoma City.

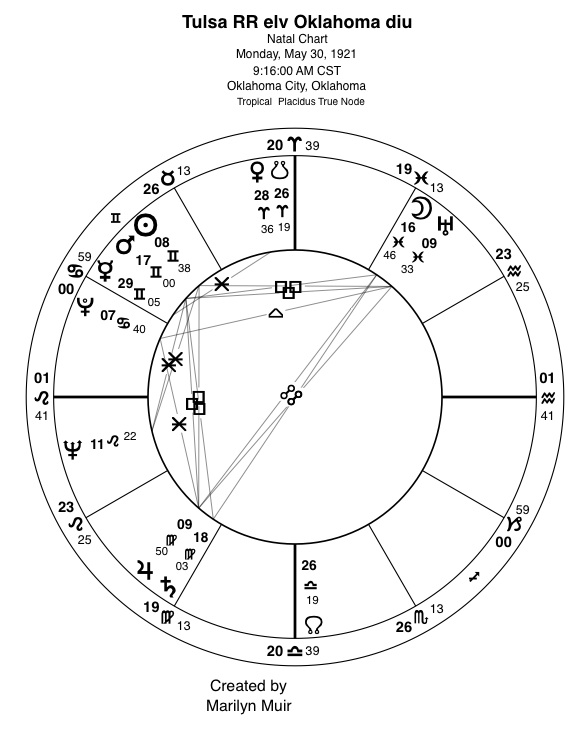

- Since we have a relocated time of 9:16 AM CST we can also research that with Oklahoma City listed as the state capital. Research should include all three charts to determine which provides the most value. So all three charts are cast for a single day event at two locations.

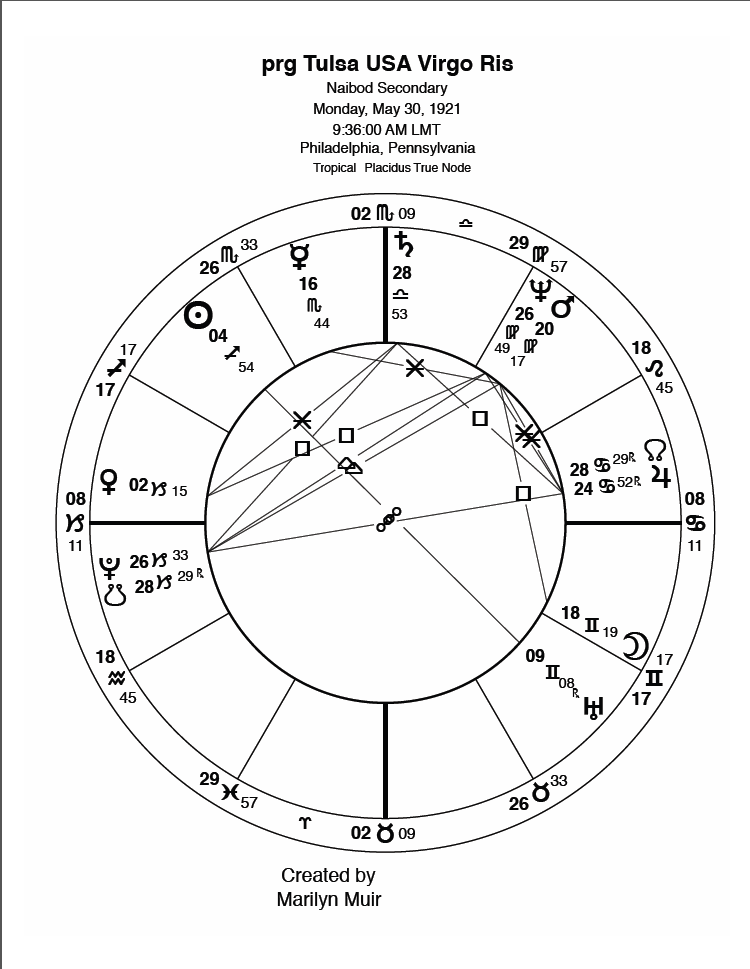

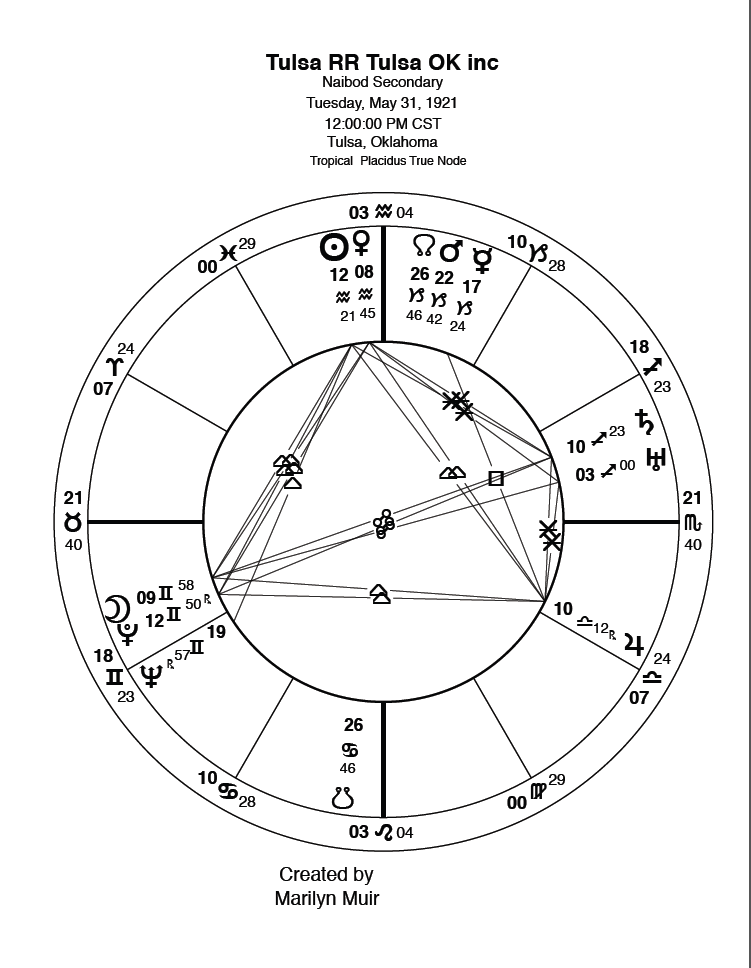

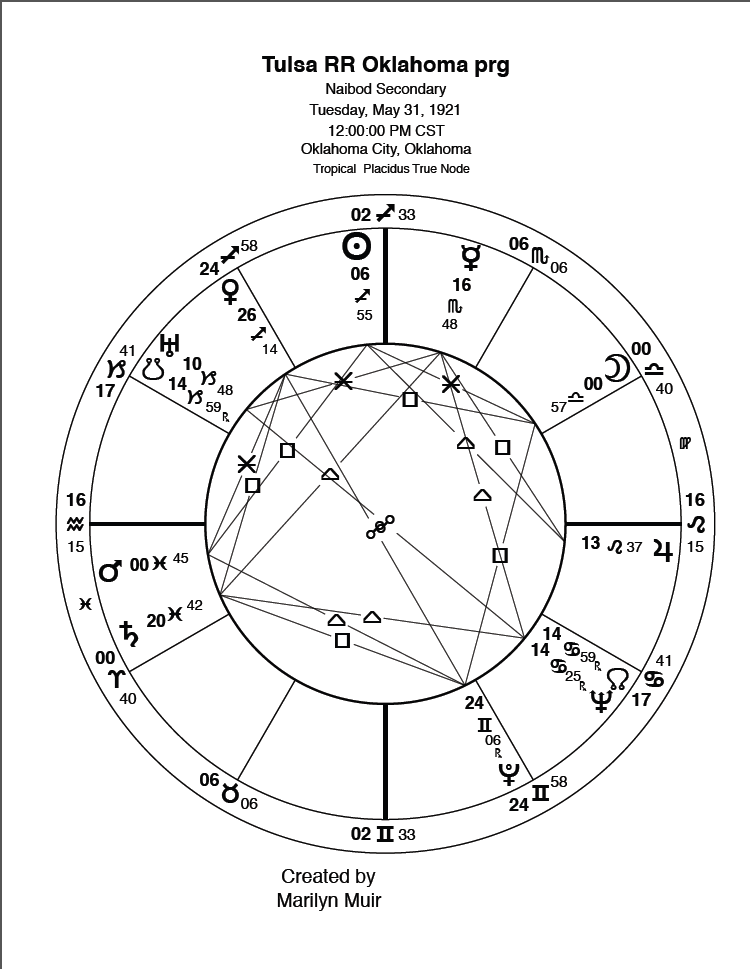

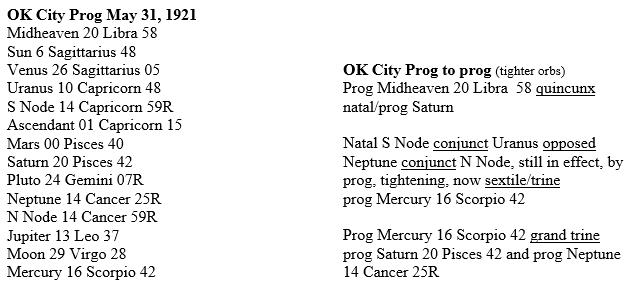

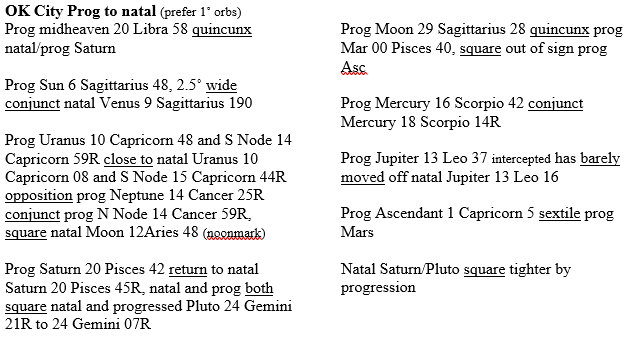

- Each of these charts must be progressed to the event (race riot date).

- A diurnal chart for the riot date is needed for each of these charts as well.

Documents:

- Tulsa Race Riot report by Oklahoma Commission to study 1921 riot, original (large document not reproduced here – please use link to access http://www.okhistory.org/research/forms/freport.pdf

- Tulsa, OK Race riot astrological aspects from three statehood chart choices

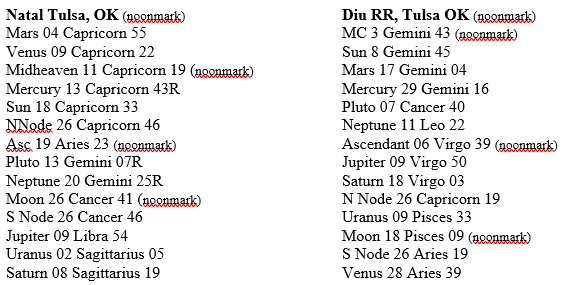

Tulsa, OK natal aspects (noonmark)

(Stellium: Capricorn 6 placements)

Mars 04 Capricorn 55 conjunct Venus 09 Capricorn 22 conjunct Midheaven 11 Capricorn 19 (noonmark), conjunct Mercury 13 Capricorn 43R, conjunct Sun 18 Capricorn 33, wide conjunct N Node 26 Capricorn 46

Stellium (wide) opposed Moon 26 Cancer 41 (noonmark) conjunct S Node 26 Cancer 46

Stellium and opposition square Ascendant 19 Aries 23 (noonmark), Jupiter 09 Libra 54 square

Mars/Venus/Midheaven/Mercury Capricorn

Pluto 13 Gemini 07R quincunx Venus/Midheaven/Mercury/Sun

Neptune 20 Gemini 25R quincunx Sun

Uranus 02 Sagittarius 05 wide conjunct Saturn

Saturn 08 Sagittarius 19 sextile Jupiter

Saturn 8 Sagittarius 19 opposition Pluto 13 Gemini 07R

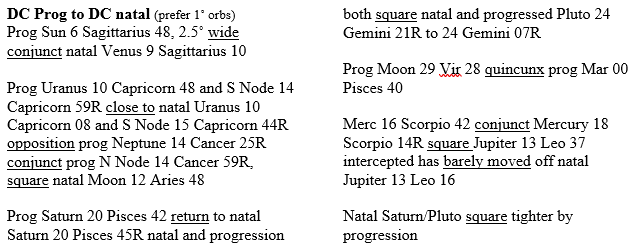

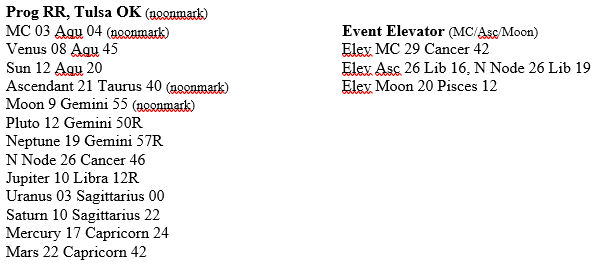

Prog RR, Tulsa OK prog to prog (1˚ orb)

MC 03 Aquarius 04 (noonmark) sextile prog Uranus

Venus 08 Aquarius 45 trine prog Moon

Ascendant 21 Taurus 40 (noonmark) trine prog Mars

Moon 9 Gemini 55 (noonmark) wide conjunct Pluto 12 Gemini 50R closer opposite Saturn 10 Sagittarius 23

Jupiter 10 Libra 12R sextile Saturn 10 Sagittarius 2

Prog Tulsa to natal Tulsa

Midheaven 03 Aquarius 04 (noonmark) sextile natal Uranus

Venus 08 Aquarius 45 trine natal Jupiter sextile natal Saturn

Sun 12 Aquarius 21 trine natal Pluto

Moon 9 Gemini 55 (noonmark) wide conjunct Pluto 12 Gemini 50R, opposition prog Saturn, trine Jupiter

Jupiter 10 Libra 12R still square natal Venus

Mercury 17 Capricorn 24 wide square natal Ascendant

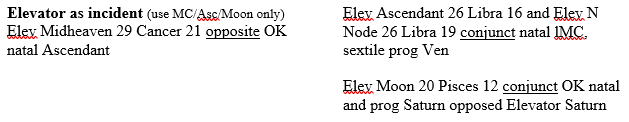

Elevator event to Tulsa natal/prog (3 positions)

Midheaven 29 Cancer 42 wide conjunct natal S Node

Ascendant 26 Libra 16 square natal Moon (noonmark) and Nodes

Moon 20 Pisces 12 square natal/prog Neptune, sextile prog ascendant (noonmark)

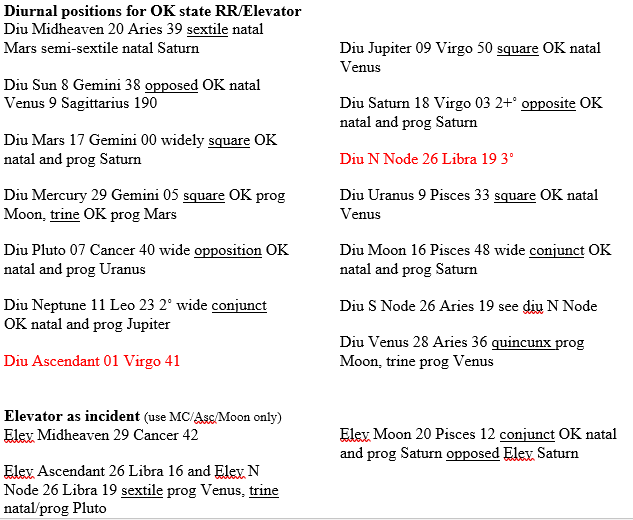

OK City state natal to Tulsa (noonmark) natal, plus three elevator incident positions

Tulsa was incorporated before OK became a state. Ordinarily you would aspect the city to the state, but in this instance you should aspect OK to Tulsa

OK Sun 23 Scorpio 07, Mercury 18 Scorpio 14R sextile Tulsa Capricorn stellium

OK Jupiter 13 Leo 16 intercepted sextile Tulsa Pluto

OK S Node 15 Capricorn 44R conjunct Tulsa Mercury

OK Uranus 10 Capricorn 08 conjunct Tulsa Midheaven (noonmark)/Mercury, opposition OK Neptune 14 Cancer 40R conjunct OK N Node 15 Cancer 44R

OK Moon 12 Aries 48 square Tulsa midheaven (noonmark)/Mercury, sextile Pluto

OK Venus 9 Sagittarius 10 conjunct Tulsa Saturn

OK Midheaven 6 Libra 34 conjunct Tulsa Jupiter, square Tulsa Mars/Venus conjunction

OK Ascendant 19 Sagittarius 20 opposite Tulsa Neptune

OK Saturn 20 Pisces 45R square Tulsa Neptune

3 Elevator positions (midheaven, ascendant, Moon)

Elev Midheaven 29 Cancer 42

Elev Ascendant 26 Libra 16, N Node 26 Libra 19

Elev Moon 20 Pisces 12

Elev Midheaven 29 Cancer 42 widely conjunct Tulsa (noonmark) S Node 26 Cancer 41 and (noonmark) Moon 26 Cancer 41 square Elev Ascendant 26 Libra 16 and N Node 26 Libra 19

Elev Moon 20 Pisces 23 conjunct OK Saturn 20 Pisces 45R, square OK Ascendant 19 Sagittarius 20, OK Pluto 24 Gemini 21R, and Tulsa Neptune 20 Gemini 25R

An event such as the Tulsa RR will show up as a stand-alone event, in the charts of those directly affected, in the chart of the city and of the state in which the event occurred, and in the country in which the event occurred. We are casting a very wide net. As the scope broadens the impact must become very specific because there is more than one event occurring in a city, a state, a country at any single time. To simplify the procedure I would start with the event itself and the transits in effect and work my way backwards into the increasingly broader pictures.

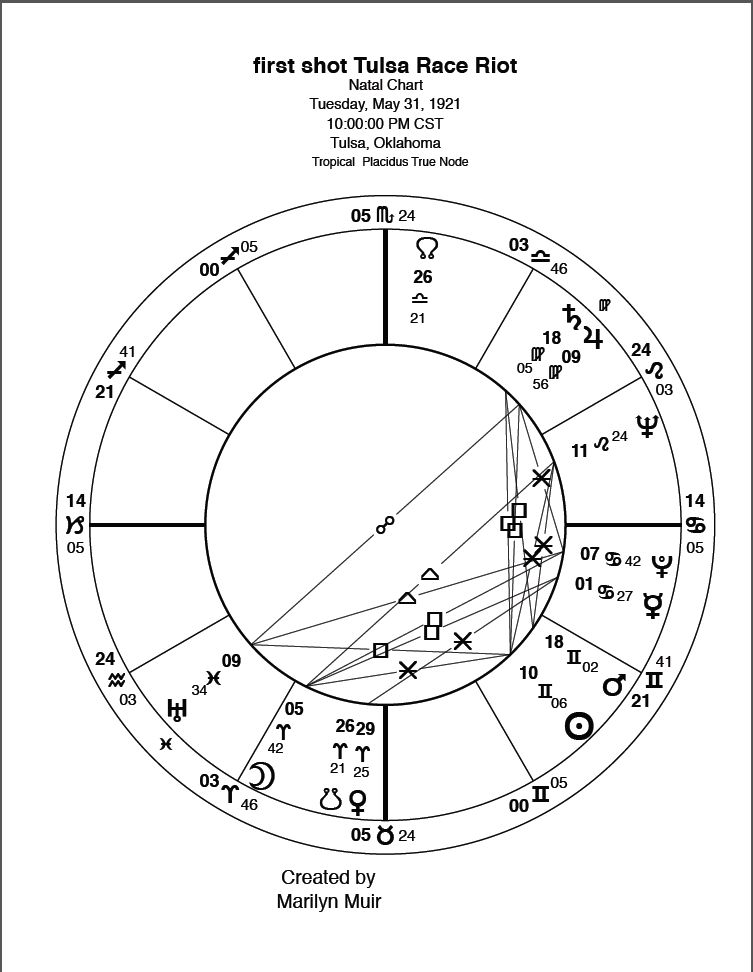

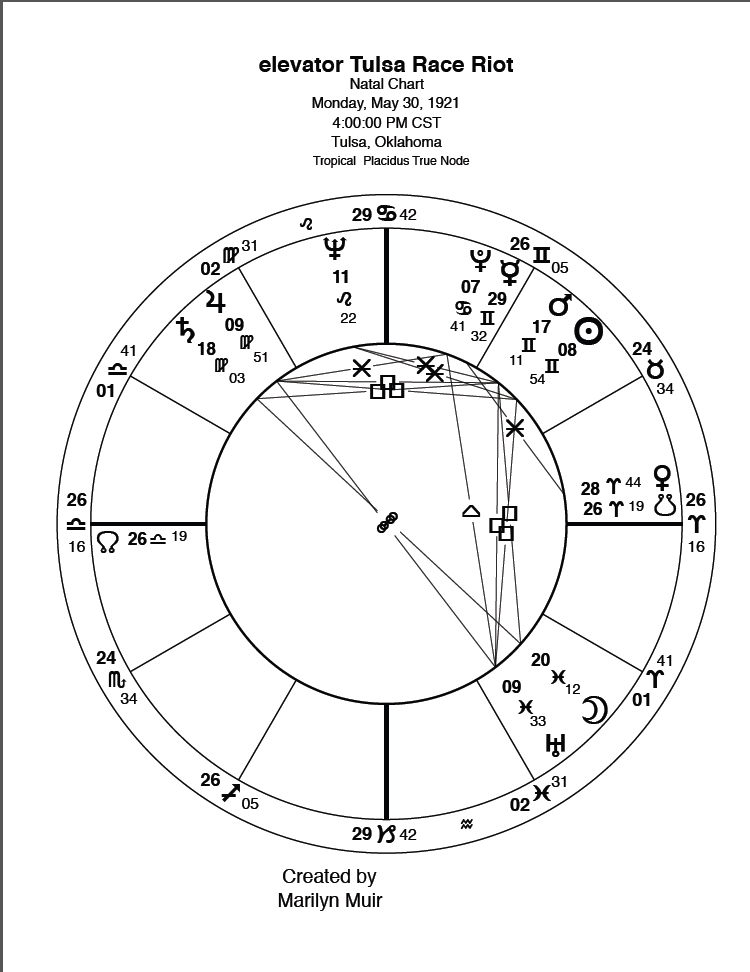

EventThe incident in the elevator, whether it be an innocent trip and fall or something else, whatever it was, we will probably never actually know what occurred. Time given was just after 4 PM according to the article. The elevator chart was set for 4:00 pm CST in Tulsa, OK.

I concentrated on hard aspects because of the nature of the event. Synastry aspects between natal charts allow for wider aspects. I personally usually allow 5˚. Transits to natal charts require much tighter aspect orbs. An event chart is technically a transit chart. I usually look for 1˚ perhaps 2˚ transit aspect orbs to any natal chart with closer being better. The outer transits require a little fudge factor. Why? An outer planet covers a few degrees during its station and retrograde period. That range of degrees is active from the first contact to the last contact even if it is not tight at the moment of the event. The contact cannot be discounted. It exists. This does complicate timing but is still a valid aspect and should not be ignored.

Event Sun 8 Gemini 54 to the minute of the US natal Uranus, 2 minutes from the US MC

Event Jupiter 9 Virgo 51 square US natal Uranus and Midheaven 1˚

Event Uranus 9 Pisces 33 square US natal Uranus and Midheaven 1˚

Event Jupiter 9 Virgo 51 conjunct US natal Ascendant 2˚

Event Uranus 9 Pisces 33 opposed US metal Ascendant 2˚

Event Pluto 7 Cancer 41 conjunct US Jupiter 2˚ and widely conjunct US Venus 5˚

Event IC 29 Capricorn 42 conjunct US Pluto 2˚

Event Saturn 18 Virgo 03 widely conjunct US Neptune 4˚

Event Mars 17 Gemini 11 widely square US Neptune 5˚ and US Mars 4˚

Event Ascendant/S Node 26 Libra 16-19 was square US Pluto 1˚ and U.S. Mercury 6˚

Event Venus 28 Libra 44 was square US Pluto 1˚

Event Moon 20 Pisces 12 was opposite US Neptune 2˚ and square US Mars 1˚

Event Neptune 11 Leo 22 widely conjunct US N Node 5˚

US natal Moon, Sun, and Saturn (3) do not evidence a close direct transit (event).

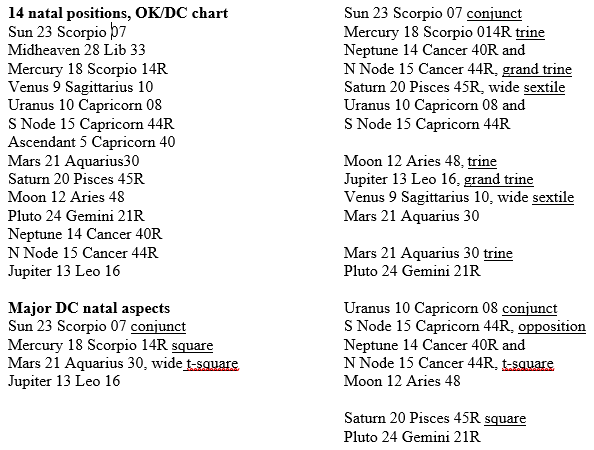

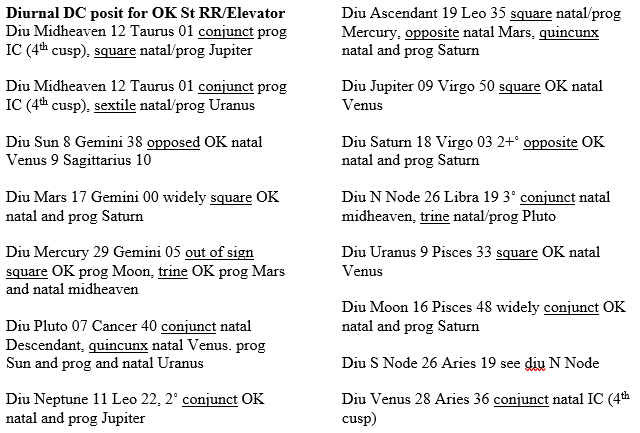

Looking at the listed event/US actual hits, what shows up in the OK City statehood chart?

OK Venus 9 Sagittarius 10 opposed US Uranus/Midheaven 1˚

OK Ascendant 19 Sagittarius 20 square US Neptune 2˚

OK Saturn 20 Pisces 45R opposed US Neptune 2˚

OK Pluto 24 Gemini 21R opposed US Neptune 2˚

OK Saturn 20 Pisces 45R square US Mars half˚

OK Pluto 24 Gemini 27R square US Mars 4˚

What in the OK chart connects with the missing elements (3) in the US Virgo rising chart?

OK Mars 21 Aquarius 30 conjunct US Moon 1˚

OK Mercury 18 Scorpio 14R conjunct US Moon 4.5˚

OK Midheaven 6 Libra 34 square U.S. Jupiter 1˚, square U.S. Venus 4˚

OK Neptune 14 Cancer 40R and N Node 15 Cancer 44R conjunct US Sun 2-3˚

OK Neptune 14 Cancer 40R and N Node 15 Cancer 44R square US Saturn 0-1˚

OK Uranus 10 Capricorn 08 oppose US Sun 3˚

OK Uranus 10 Capricorn 08 square US Saturn 4˚

OK Moon 12 Aries 48 tight square US Sun, oppose US Saturn 2˚

Again looking at the listed US hits, what connections shows up in Tulsa city incorporation chart?

Tulsa Saturn 8 Sagittarius 19 oppose US Midheaven/Uranus half˚

Tulsa Mars 4 Capricorn 55 oppose US Jupiter 1˚, oppose US Venus 2˚

Tulsa Venus 9 Capricorn 22 oppose US Jupiter 4˚

Tulsa Neptune 20 Gemini 25R conjunct US Mars half˚, square US Ascendant 2˚

Tulsa N Node 26 Capricorn 46 conjunct US Pluto 1˚

Tulsa Moon 26 Cancer 41 opposite US Pluto 1˚

What else in the OK chart connects with the missing elements (3) in the US Virgo rising chart

Tulsa (noonmark) Misheaven 11 Capricorn 19 oppose US Sun 2˚ square US Saturn 3˚

Tulsa Venus 9 Capricorn 22 oppose US Sun 4˚ square US Saturn 5˚

Tulsa Mercury 13 Capricorn 43R oppose US Sun 3/4˚ square US Saturn 1˚

Tulsa Jupiter 9 Libra 54 US square US Sun 3˚, trine US midheaven/Uranus 1˚

Note complex pattern: Tulsa Jupiter 9 Libra 54 square Venus 9 Capricorn 22 aspects close to the US Jupiter 5 Cancer 52, Sun 13 Cancer 01 and Saturn 14 Libra 48 and the OK Cancer/Capricorn axis.

Just in case you do not realize the enormity of what we are examining:

A chart (timed) for a country dated 1776, ties amazingly well into a (timed) tragic event dated 1921, an incorporation of a city dated 1898 (noonmark) and the granting of statehood dated 1907. And they say this stuff does not work!

- Tulsa research notes

About Tulsa

https://www.cityoftulsa.org/our-city/about-tulsa.aspx

Tulsa was incorporated as a municipality on January 8, 1898. … the city grew quickly, reaching a population of 7,298 by the time of Oklahoma statehood in 1907.

Oklahoma Statehood, November 16, 1907www.archives.gov/legislative/features/oklahoma

Oklahoma Statehood, November 16, 1907. Housed in the historical records of the U.S. House of Representatives and the United States Senate at the Center for …

timeline with detail http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tulsa_race_riot

Location “Black Wall Street” of Greenwood, Tulsa, Oklahoma

Coordinates

36°09′34″N 95°59′11″W

Date May 31 – June 1, 1921

Weapons Guns, incendiary devices

Deaths 39 officially

Other estimates range from 55 to 300

Non-fatal injuries Over 800

Perpetrators White residents

Oklahoma National Guard

The Tulsa race riot was a large-scale, racially motivated conflict on May 31 and June 1, 1921, in which a group of white people attacked the black community of Tulsa, Oklahoma. It resulted in the Greenwood District, also known as ‘the Black Wall Street'[1] and the wealthiest black community in the United States, being burned to the ground.

During the 16 hours of the assault, more than 800 people were admitted to local white hospitals with injuries (the two black hospitals were burned down), and police arrested and detained more than 6,000 black Greenwood residents at three local facilities.[2]:108–109 An estimated 10,000 blacks were left homeless, and 35 city blocks composed of 1,256 residences were destroyed by fire. The official count of the dead by the Oklahoma Department of Vital Statistics was 39, but other estimates of black fatalities varies from 55 to about 300.[2]:108, 228 [3]

The events of the riot were long omitted from local and state histories. “The Tulsa race riot of 1921 was rarely mentioned in history books, classrooms or even in private. Blacks and whites alike grew into middle age unaware of what had taken place.”[4] With the number of survivors declining, in 1996, the state legislature commissioned a report to establish the historical record of the events, and acknowledge the victims and damages to the black community. Released in 2001, the report included the commission’s recommendations for some compensatory actions, most of which were not implemented by the state and city governments. The state has passed legislation to establish some scholarships for descendants of survivors, economic development of Greenwood, and a memorial park to the victims in Tulsa. The latter was dedicated in 2010.

The riot occurred in the racially and politically tense atmosphere of post-World War I northeastern Oklahoma. The territory, which was declared a state on November 16, 1907, had received many settlers from the South who had been slaveholders before the American Civil War. In the early 20th century, lynchings were common in Oklahoma, as part of a continuing effort by whites to assert and maintain white supremacy. Between the declaration of statehood and the Tulsa race riot 13 years later, 31 persons were lynched in Oklahoma; 26 were black and nearly all were men and boys. During the twenty years following the riot, the number of lynchings statewide fell to two.[5]

The newly created state legislature passed racial segregation laws, commonly known as Jim Crow laws, as one of its first orders of business. Its 1907 constitution and laws had voter registration rules that disfranchised most blacks; this also barred them from serving on juries or in local office, a situation that lasted until the federal Voting Rights Act of 1965, part of civil rights legislation passed by the US Congress. Major cities passed their own restrictions.[2]

On August 16, 1916, Tulsa passed an ordinance forbidding blacks or whites from residing on any block where three-fourths or more of the residents were of the other race. This made residential segregation mandatory in the city. Although the United States Supreme Court declared the ordinance unconstitutional the next year, it remained on the books.[2]

As cities absorbed returning veterans into the labor market following World War I, there was social tension and anti-black sentiment. At the same time, black veterans pushed to have their civil rights enforced, believing they had earned full citizenship by military service. In what became known as “Red Summer” of 1919, industrial cities across the Midwest and North had severe race riots, often led by ethnic whites among recent immigrant groups, who competed most with blacks for jobs. In Chicago and some other cities, blacks defended themselves for the first time with force but were outnumbered.

Northeastern Oklahoma had an economic slump that put men out of work. Since 1915, the Ku Klux Klan was growing in urban chapters across the country, particularly since veterans had been returning from the war. It first appeared in Oklahoma in a major way later that year on August 12, 1921, less than three months after the Tulsa riot.[6] The historian Charles Alexander estimated that by the end of 1921, Tulsa had 3,200 residents in the Klan.[6] The city population was 72,000 in 1920.[7]

The traditionally black district of Greenwood in Tulsa 36°09′34″N 95°59′11″W had a commercial district so prosperous it was known as “the Negro Wall Street” (now commonly referred to as “the Black Wall Street”). Blacks had created their own businesses and services in their enclave, including several groceries, two independent newspapers, two movie theaters, nightclubs, and numerous churches. Professional black doctors, dentists, lawyers and clergy served the community. Because of residential segregation in the city, most classes of blacks lived together in Greenwood. They selected their own leaders, and there was capital formation within the community. In the surrounding areas of northeastern Oklahoma, blacks also enjoyed relative prosperity and participated in the oil boom.[8]Monday, May 30, 1921

Encounter in the elevator

Sometime around or after 4 p.m., nineteen-year-old Dick Rowland, a black shoeshiner employed at a Main Street shine parlor, entered the only elevator of the nearby Drexel Building, at 319 South Main Street, to use the top floor restroom, which was restricted to blacks. He encountered Sarah Page, the 17-year-old white elevator operator who was on duty. The two likely knew each other at least by sight, as this building was the only one nearby with a washroom which Rowland had express permission to use, and the elevator operated by Page was the only one in the building. A clerk at Renberg’s, a clothing store located on the first floor of the Drexel, heard what sounded like a woman’s scream and saw a young black man rushing from the building. The clerk went to the elevator and found Page in what he said was a distraught state. Thinking she had been assaulted, he summoned the authorities.[9]

The 2000 official commission report notes that it was unusual for both Rowland and Page to be working downtown on Memorial Day, when most stores and businesses were closed. It suggests that Rowland had a simple accident, such as tripping and steadying himself against the girl, or perhaps they were lovers and had a quarrel.[10]

Whether – and to what extent – Dick Rowland and Sarah Page knew each other has long been a matter of speculation. It seems reasonable that they would have least been able to recognize each other on sight, as Rowland would have regularly ridden in Page’s elevator on his way to and from the restroom. Others, however, have speculated that the pair might have been lovers – a dangerous and potentially deadly taboo, but not an impossibility… Whether they knew each other or not, it is clear that both Dick Rowland and Sarah Page were downtown on Monday, May 30, 1921 – although this, too, is cloaked in some mystery. On Memorial Day, most – but not all – stores and businesses in Tulsa were closed. Yet, both Rowland and Page were apparently working that day…

What happened next is anyone’s guess. After the riot, the most common explanation was that Dick Rowland tripped as he got onto the elevator and, as he tried to catch his fall, he grabbed onto the arm of Sarah Page, who then screamed. It also has been suggested that Rowland and Page had a lovers’ quarrel. However, it simply is unclear what happened. Yet, in the days and years that followed, everyone who knew Dick Rowland agreed on one thing: that he would never have been capable of rape.[10]

The word rape was rarely used in newspapers or academia in the early 20th century. Instead, assault was used to describe such an attack.[2]

A brief investigation

Although the police likely questioned Page, no written account of her statement has surfaced. It is generally accepted that they determined what happened between the two teenagers was something less than an assault. The authorities conducted a rather low-key investigation rather than launching a man-hunt for her alleged assailant. Afterward, Page told the police that she would not press charges.[2]

Regardless of whether assault had occurred, Rowland had reason to be fearful, as at the time, such an accusation alone put him at risk for attack by racist white men. Realizing the gravity of the situation, Rowland fled to his mother’s house in the Greenwood neighborhood.[10]

Suspect arrested

On the morning after the incident, Detective Henry Carmichael and Henry C. Pack, a black patrolman, located Rowland on Greenwood Avenue and detained him. Pack was one of two black officers among the city’s approximately 45-man police force.[2] Rowland was initially taken to the Tulsa city jail at First and Main. Late that day, Police Commissioner J. M. Adkison said he had received an anonymous telephone call threatening Rowland’s life. He ordered Rowland transferred to the more secure jail on the top floor of the Tulsa County Courthouse.[11]

Word quickly spread in Tulsa’s legal circles. As patrons of the shine shop where Rowland worked, many attorneys knew him. Witnesses recounted hearing several attorneys defending him in personal conversations with one another. One of the men said, “Why, I know that boy, and have known him a good while. That’s not in him.”[12]

Newspaper coverage

The Tulsa Tribune, one of two white-owned papers published in Tulsa, broke the story in that afternoon’s edition with the headline: “Nab Negro for Attacking Girl In an Elevator”, describing the alleged incident. According to some witnesses, the same edition of the Tribune included an editorial warning of a potential lynching of Rowland, and entitled “To Lynch Negro Tonight”. The paper was known at the time to have a “sensationalist” style of news writing. All original copies of that issue of the paper have apparently been destroyed, and the relevant page is missing from the microfilm copy, so the exact content of the column (and whether it existed at all) remains in dispute.[13][14][15]

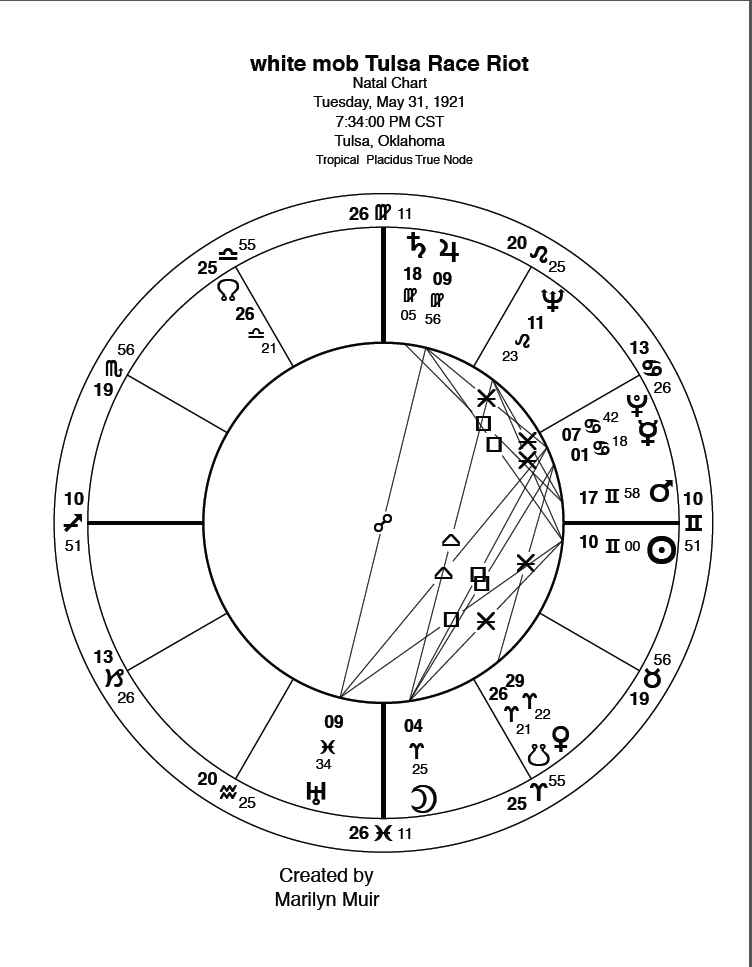

Stand-off at the courthouse

The afternoon edition of the Tribune hit the streets shortly after 3 p.m., and soon news of the potential lynching spread. By 4 p.m., the local authorities were on alert. White people began congregating at and near the Tulsa County Courthouse. By sunset at 7:34 p.m., the several hundred whites assembled outside the courthouse appeared to have the makings of a lynch mob. Willard M. McCullough, the newly elected sheriff of Tulsa County, was determined to avoid events such as the 1920 lynching of Roy Belton in Tulsa, which occurred during the term of his predecessor.[16] The sheriff took steps to ensure the safety of Rowland. McCullough organized his deputies into a defensive formation around Rowland, who was terrified. The sheriff positioned six of his men, armed with rifles and shotguns, on the roof of the courthouse. He disabled the building’s elevator, and had his remaining men barricade themselves at the top of the stairs with orders to shoot any intruders on sight. The sheriff went outside and tried to talk the crowd into going home, but to no avail. According to an account by Ellsworth, the sheriff was “hooted down”.[17]

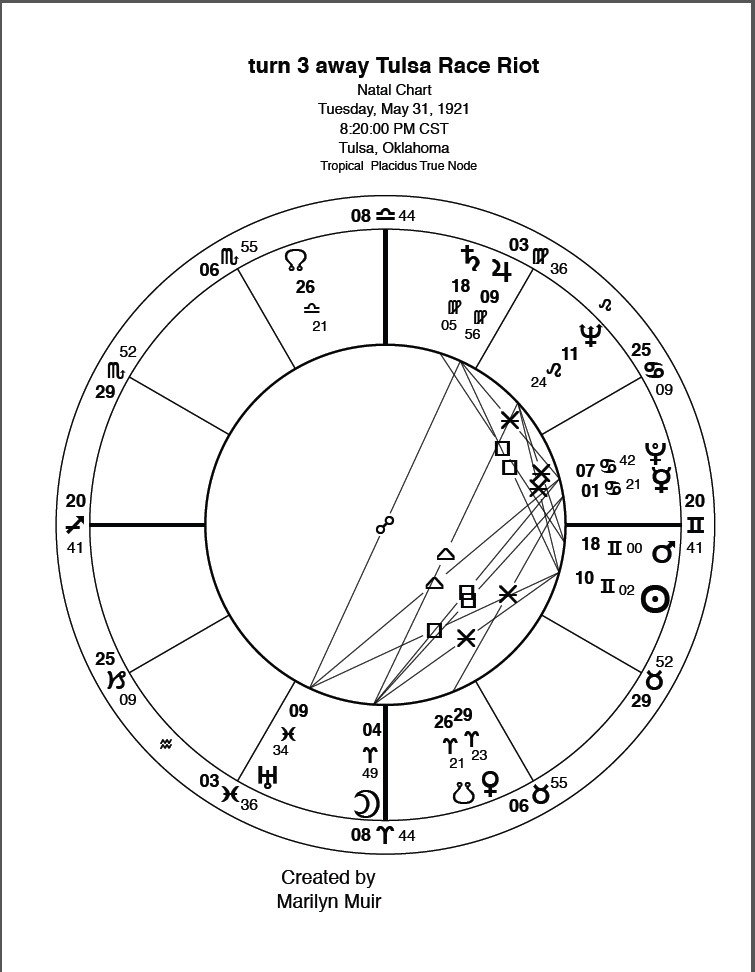

About 8:20 p.m., three white men entered the courthouse, demanding that Rowland be turned over to them. Although vastly outnumbered by the growing crowd out on the street, Sheriff McCullough was determined to prevent another lynching and turned the men away.[2]

Offer of help [meanwhile]

A few blocks away on Greenwood Avenue, members of the black community were gathering to discuss the situation at the courthouse. Given the recent lynching of Roy Belton, a white man accused of murder, they believed that Rowland was greatly at risk. The community was determined to prevent the lynching of another young black man, but divided about the tactics to be used. Young World War I veterans were preparing for a battle by collecting guns and ammunition. Older, more prosperous men feared a destructive confrontation that likely would cost them dearly. O. W. Gurley walked to the courthouse, where the sheriff assured him that there would be no lynching. Returning to Greenwood, Gurley tried to calm the group, but failed. About 7:30 p.m., a mob of approximately 30 black men, armed with rifles and shotguns, decided to go to the courthouse and support the sheriff and his deputies to defend Rowland from the mob. Assuring them that Rowland was safe, the sheriff and his black deputy, Barney Cleaver, encouraged the men to return home.[2][18]

Taking up arms

Having seen the armed blacks, some of the more than 1,000 whites at the courthouse went home for their own guns. Others headed for the National Guard armory at Sixth Street and Norfolk Avenue, where they planned to arm up. The armory contained a supply of small arms and ammunition. Major James Bell of the 180th Infantry had already learned of the mounting situation downtown and the possibility of a break-in, and he took appropriate measures to prevent this. He called the commanders of the three National Guard units in Tulsa, who ordered all the Guard members to put on their uniforms and report quickly to the armory. When a group of whites arrived and began pulling at the grating over a window, Bell went outside to confront the crowd of 300–400 men. Bell told them that the Guard members inside were armed and prepared to shoot anyone who tried to enter. After this show of force, the crowd withdrew from the armory.[2]

At the courthouse, the crowd had swollen to nearly 2,000, many of them now armed. Several local leaders, including Reverend Charles W. Kerr, pastor of the First Presbyterian Church, tried to dissuade mob action. The chief of police, John A. Gustafson, later claimed that he tried to talk the crowd into going home.[17]

Anxiety on Greenwood Avenue was rising. The black community was worried about the safety of Rowland. Small groups of armed black men began to venture toward the courthouse in automobiles, partly for reconnaissance, and to demonstrate they were prepared to take necessary action to protect Rowland.[17]

Many white men interpreted these actions as a “Negro uprising” and became concerned. Eyewitnesses reported gunshots, presumably fired into the air, increasing in frequency during the evening.[17]

Second offer

In Greenwood, rumors began to fly – in particular, a report that whites were storming the courthouse. Shortly after 10 p.m., a second, larger mob of approximately seventy-five armed black men decided to go to the courthouse. They offered their support to the sheriff, who declined their help. According to witnesses, a white man is alleged to have told one of the armed black men to surrender his pistol. The man refused, and a shot was fired. That first shot may have been accidental, or meant as a warning shot; it was a catalyst for an exchange of gunfire.[19]

The riot

The gunshots triggered an almost immediate response by the white men, many of whom fired on the blacks, who continued firing back at the whites. The first “battle” was said to last a few seconds or so, but took a toll, as several white and black lay dead or dying in the street. The black contingent retreated toward Greenwood. A rolling gunfight ensued. The armed white mob pursued the black group toward Greenwood, with many stopping to loot local stores for additional weapons and ammunition. Along the way innocent bystanders, many of whom were leaving a movie theater after a show, were caught off guard by the mob and began fleeing. Panic set in as the white mob began firing on any blacks in the crowd. The mob also shot and killed at least one white man in the confusion.[17]

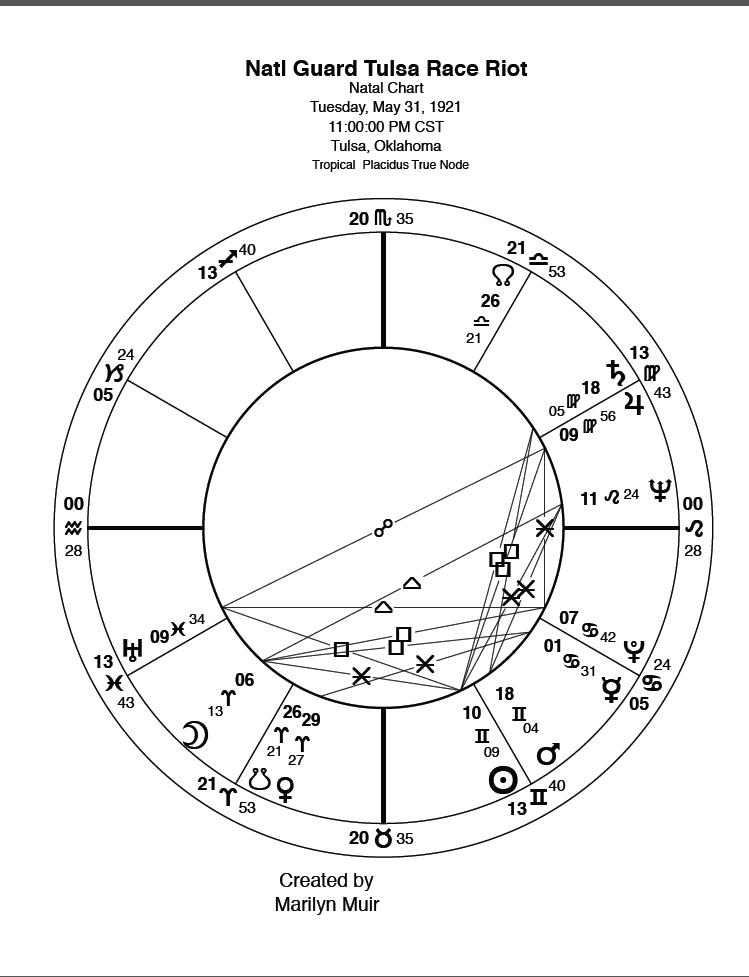

At around 11 p.m., members of the Oklahoma National Guard unit began to assemble at the armory to organize a plan to subdue the rioters. Several groups were deployed downtown to set up guard at the courthouse, police station, and other public facilities. Members of the local chapter of the American Legion joined in on patrols of the streets. The forces appeared to have been deployed to protect the white districts adjacent to Greenwood. This manner of deployment led to the National Guard being set in apparent opposition to the black community. The National Guard began rounding up blacks who had not returned to Greenwood and taking them to the Convention Hall on Brady Street for detention.[17]

Many prominent Tulsa whites also participated in the riot, including Tulsa founder and KKK member W. Tate Brady who participated in the riot as a night watchman. He reported seeing “five dead negroes,” including one man who was dragged behind a car by a noose around his neck.[20]

At around midnight, white rioters again assembled outside the courthouse. It was a smaller group but more organized and determined. They shouted in support of a lynching. When they attempted to storm the building, the sheriff and his deputies turned them away and dispersed them.

Throughout the early morning hours, groups of armed whites and blacks squared off in gunfights. At this point the fighting was concentrated along sections of the Frisco tracks, a dividing line between the black and white commercial districts. A rumor circulated that more blacks were coming by train from Muskogee to help with an invasion of Tulsa. At one point, passengers on an incoming train were forced to take cover on the floor of the train cars, as they had arrived in the midst of crossfire, with the train taking hits on both sides.[2]

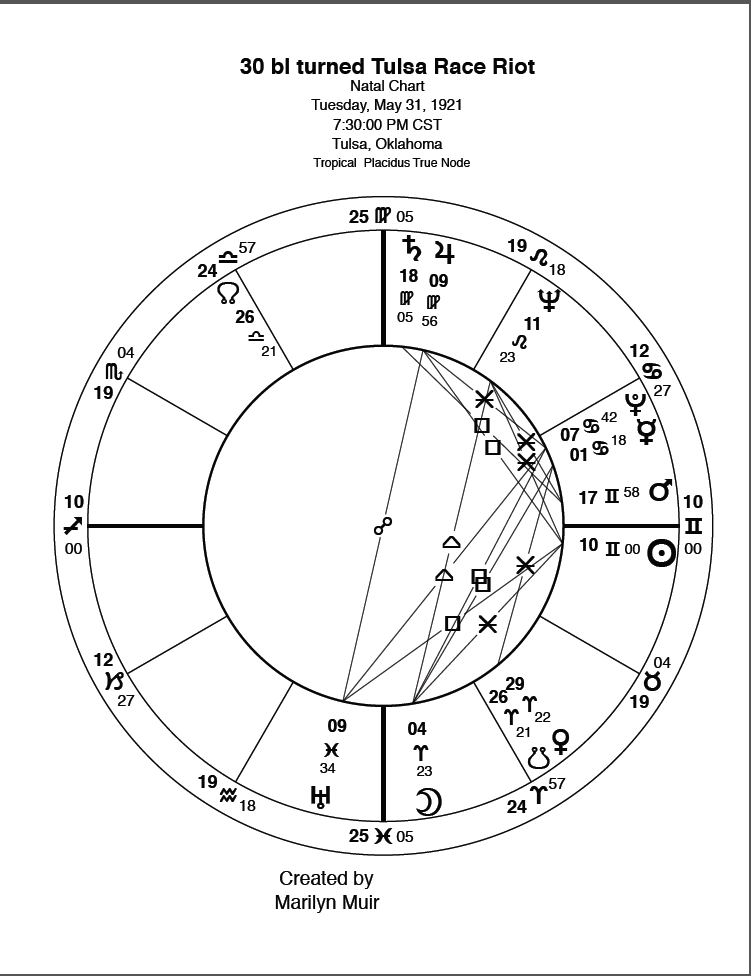

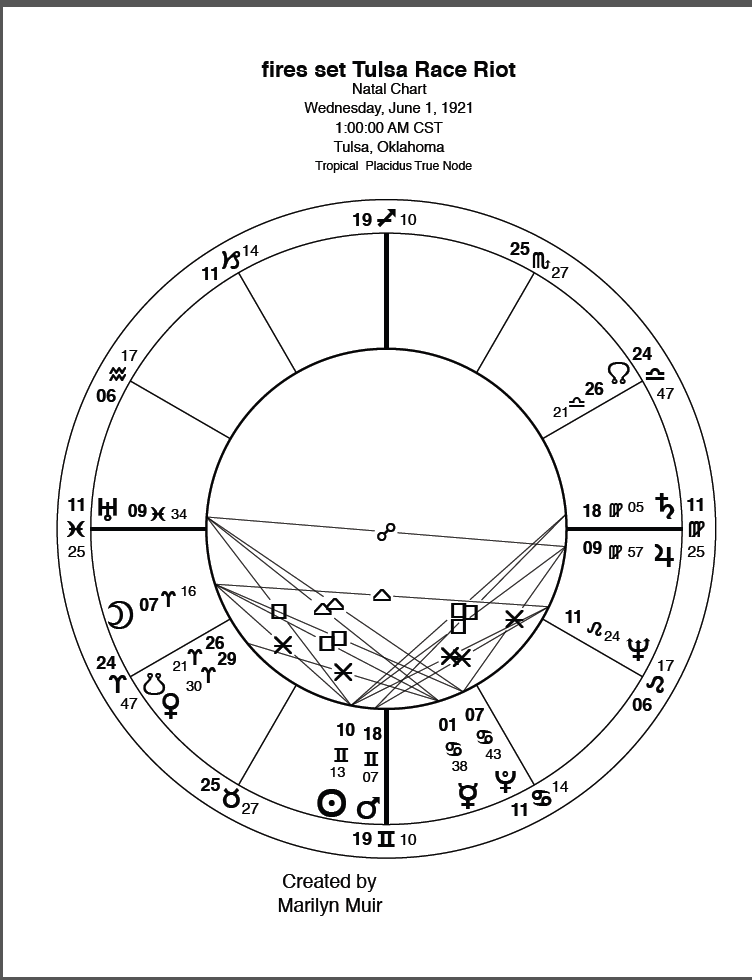

Small groups of whites made brief forays by car into Greenwood, indiscriminately firing into businesses and residences. They often received return fire. Meanwhile, white rioters threw lighted oil rags into several buildings along Archer street, igniting them.[2]

Fires begin

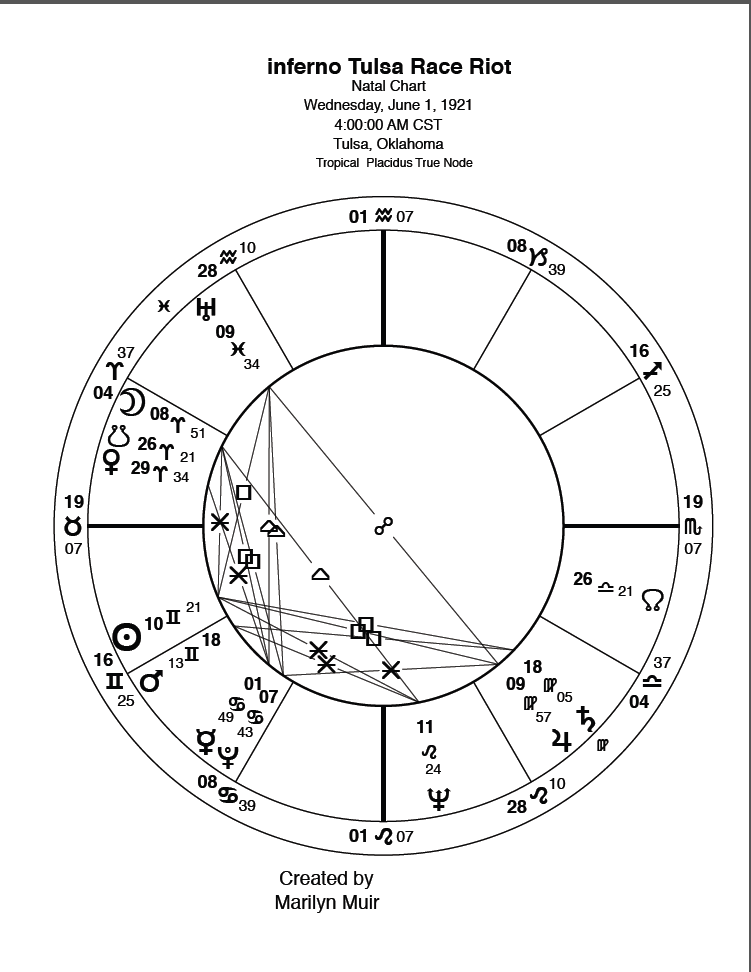

At around 1 a.m., the white mob began setting fires, mainly in businesses on commercial Archer Street at the southern edge of the Greenwood district. As crews from the Tulsa Fire Department arrived to put out fires, they were turned away at gunpoint.[2] By 4 a.m., an estimated two-dozen black-owned businesses had been set ablaze.

As news traveled among Greenwood residents in the early morning hours, many began to take up arms in defense of their community, while others began a mass exodus from the city. Throughout the night both sides continued fighting, sometimes only sporadically.

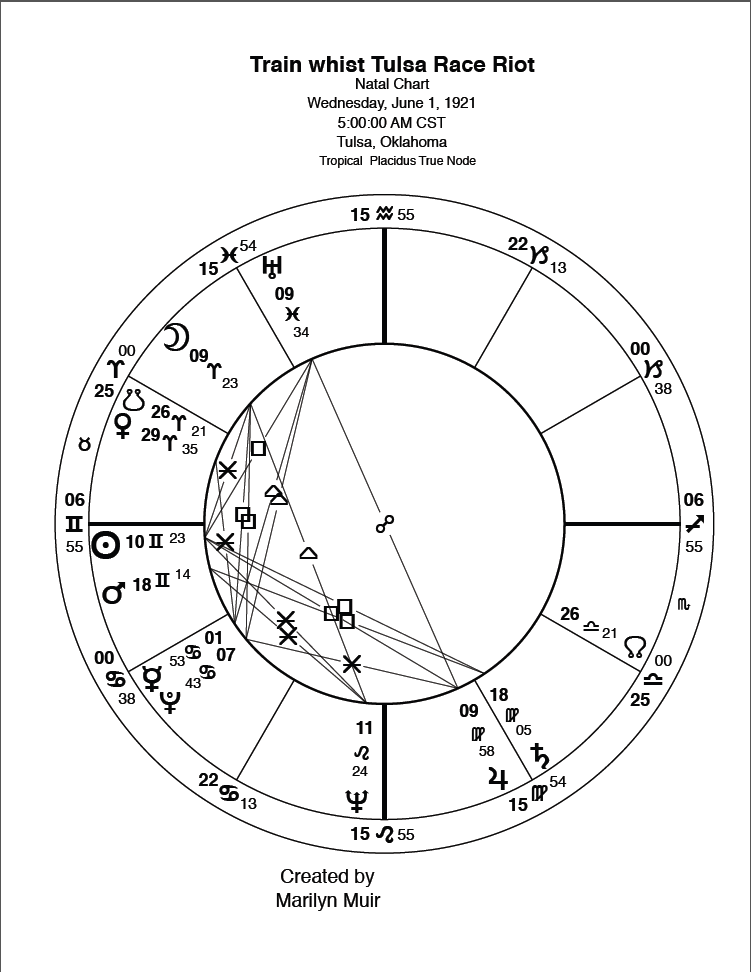

Daybreak

Upon the 5 a.m. sunrise, reportedly a train whistle was heard (Hirsch said it was a siren). Many believed this to be a signal for the rioters to launch an all-out assault on Greenwood. A white man stepped out from behind the Frisco depot and received a fatal bullet from a sniper in Greenwood. Crowds of rioters poured from places of shelter, on foot and by car, into the streets of the black community. Five white men in a car led the charge, but were killed by a fusillade of gunfire before they had gone a block.[2]

Overwhelmed by the sheer number of whites, more blacks retreated north on Greenwood Avenue to the edge of town. Chaos ensued as terrified residents fled for their lives. The rioters shot indiscriminately, and killed many residents along the way. Splitting up into small groups, they began breaking into houses and buildings, looting them and taking whatever they fancied. Several blacks later testified that whites broke into occupied homes, and ordered the residents out to the street, where they could be driven or forced to walk to detention centers.[2]

A rumor spread among the whites that the new Mount Zion Baptist Church was being used as a fortress and armory. Supposedly twenty caskets full of rifles had been delivered to the church, though no evidence was ever found.[2]

Attack by air

Numerous witness accounts described airplanes carrying white assailants, who fired rifles and dropped firebombs on buildings, homes, and fleeing families.[citation needed] The planes, six biplane two-seater trainers left over from World War I, were dispatched from the nearby Curtiss-Southwest Field outside Tulsa.[21] Law enforcement officials later stated the planes were to provide reconnaissance and protect against a “Negro uprising”.[21] Eyewitness accounts and testimony from the survivors maintained that on the morning of June 1, the planes dropped incendiary bombs and fired rifles at black residents on the ground.[21]

Several groups of blacks attempted to organize a defense, but they were overwhelmed by the number of armed whites.[citation needed] Many blacks surrendered.[citation needed] Others returned fire, and ultimately died.[citation needed] As the fires spread northward through Greenwood, countless black families continued to flee.[citation needed] Many were estimated to have died when trapped by the flames.[citation needed]

Other whites

As unrest spread to other parts of the city, many middle class white families who employed blacks in their homes as live-in cooks and servants were accosted by white rioters. They demanded that families turn over their employees to be taken to detention centers around the city. Many white families complied, and those who refused were subjected to attacks and vandalism in turn.[17]

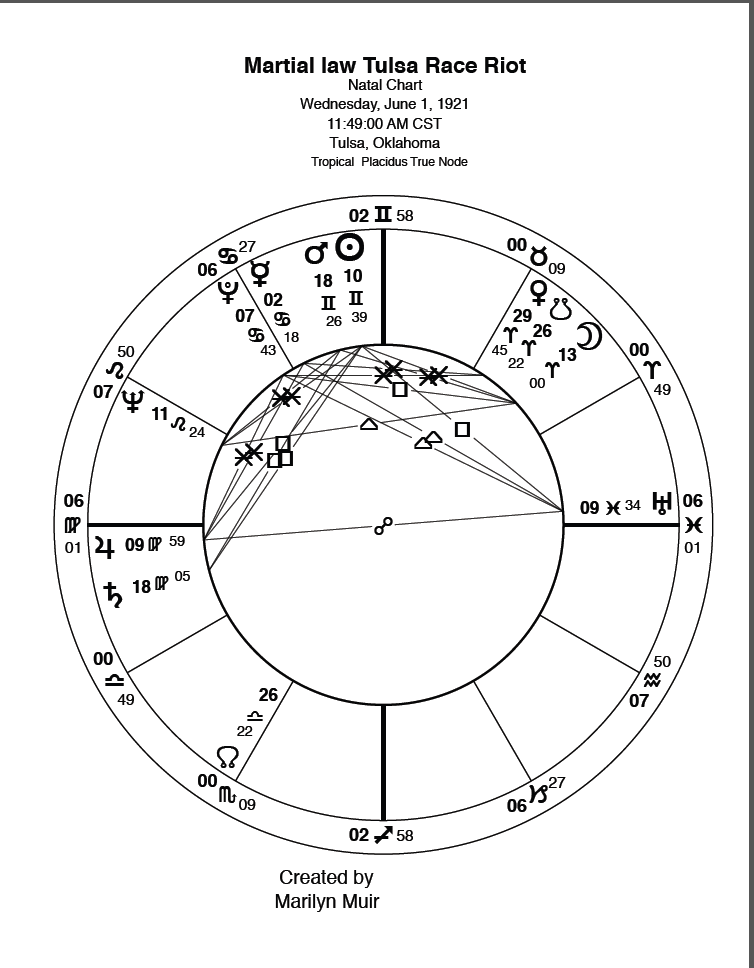

Arrival of state troops

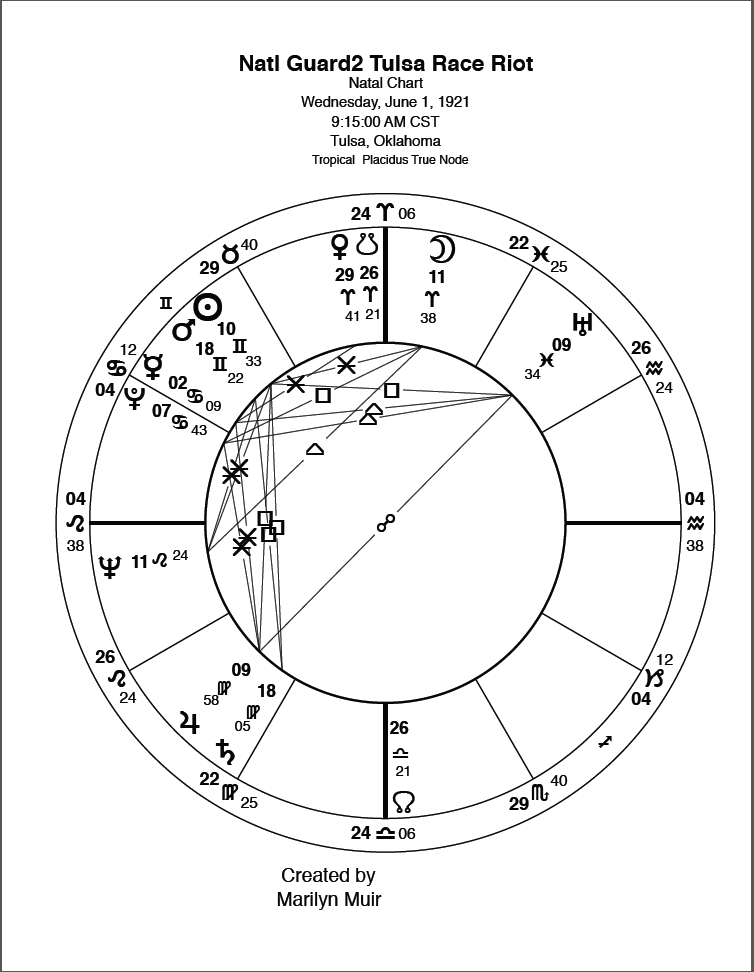

Adjutant General Charles Barrett of the Oklahoma National Guard arrived with 109 troops from Oklahoma City by special train about 9:15 a.m. He could not legally act until he had contacted all the appropriate local authorities, including the mayor, the sheriff and the police chief. Meanwhile his troops paused to eat breakfast. Barrett also summoned reinforcements from several other Oklahoma cities. By this time, most of the surviving black citizens had either fled the city or were in custody at the various detention centers. The troops declared martial law at 11:49 a.m.,[2] and by noon had managed to suppress most of the remaining violence. A 1921 letter from an Officer of the Service Company, Third Infantry, Oklahoma National Guard arriving May 31, 1921[22] and reports taking about 30-40 African Americans in custody; putting a machine gun on a truck and putting it on patrol; being fired on from Negro snipers from the “Church” and returning fire; bring fired on by white men; turning the prisoners over to deputies to take them to Police headquarters; being fired upon again by negroes and having two NCO slightly wounded;[23] searching for negroes and firearms; detailing a NCO to take 170 Negroes to the Civil authorities; and then delivering an additional 150 Negroes to the Convention Hall[24]

- President Teddy Roosevelt Signing Statehood Proclamation

Charts:

- U.S. Virgo rising natal chart plus progressed and diurnal

- Tulsa OK incorporation chart noonmark, plus progressed and diurnal

- Oklahoma state chart, DC based, timed, plus progressed and diurnal

- Oklahoma state chart, OK City, OK relocated, timed, plus progressed and diurnal

- Oklahoma state chart, noonmark, based Oklahoma City, OK, plus progressed and diurnal

- Tri-wheel of concentric rings of OK state, Tulsa riot progressed, diurnal

- The tri-wheel of concentric rings of Tulsa incorporation natal, riot progressed, diurnal

- Tulsa race riot tri-wheel shows OK state, incorporation of Tulsa, riot elevator

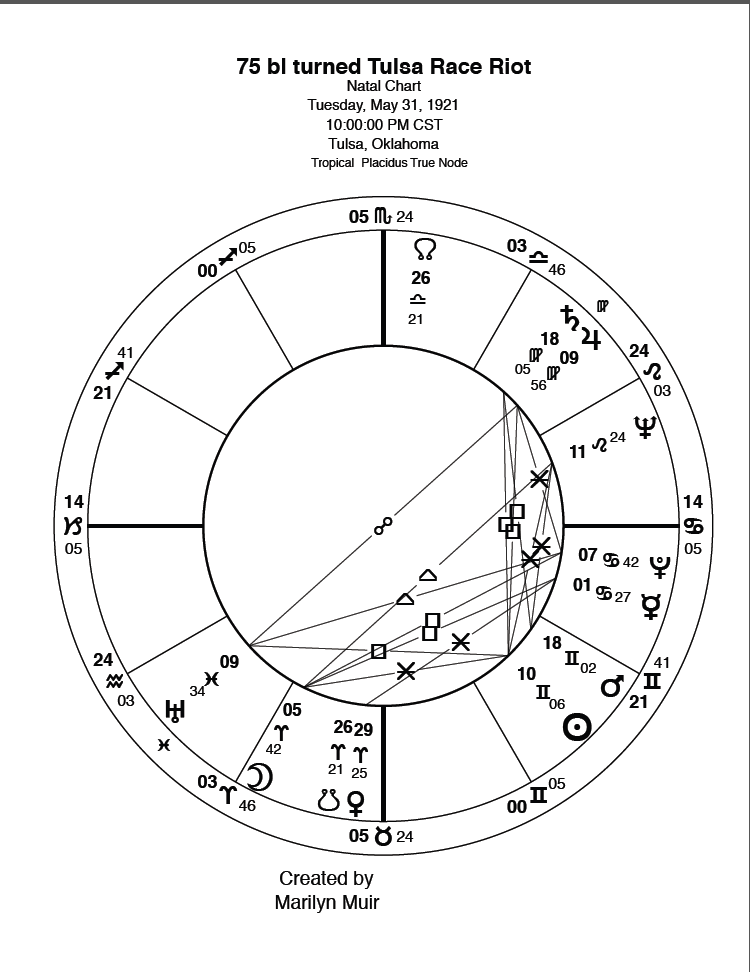

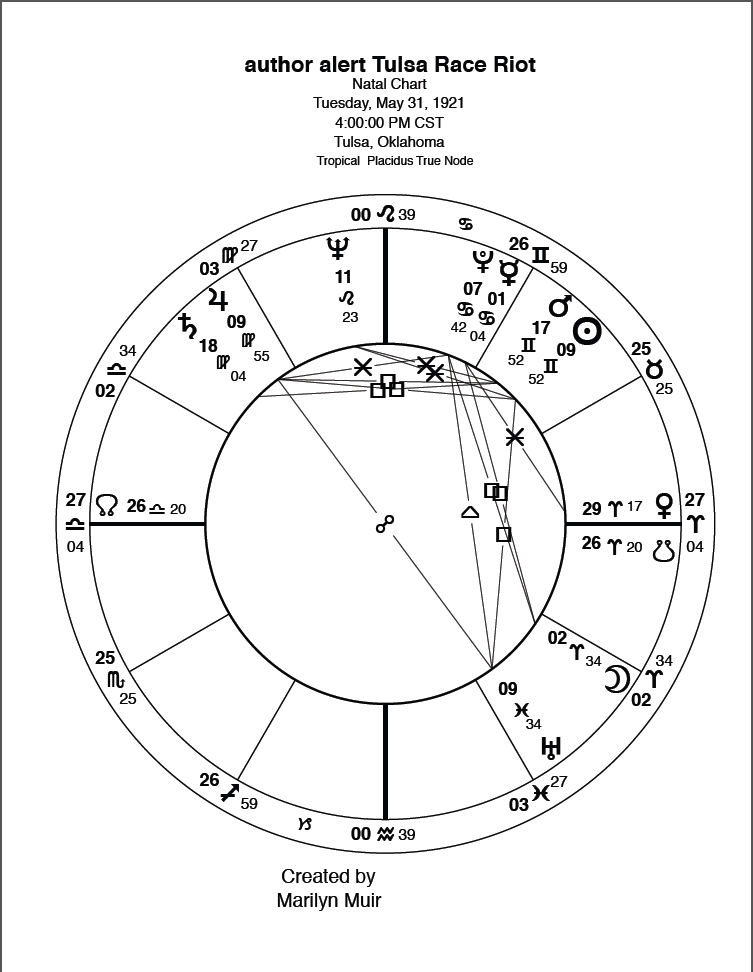

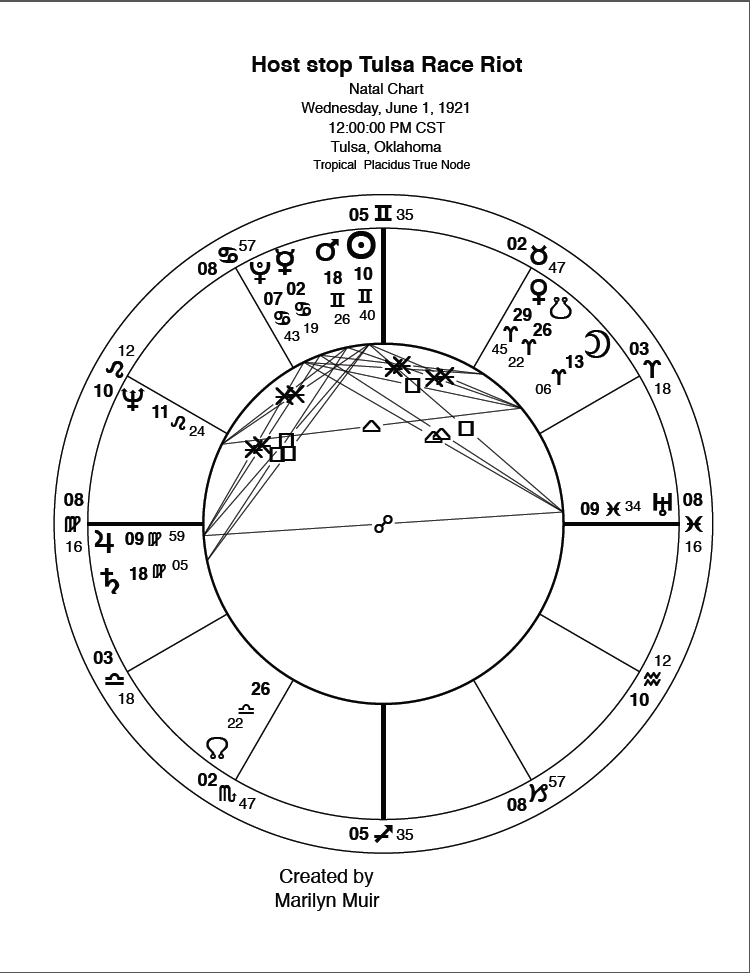

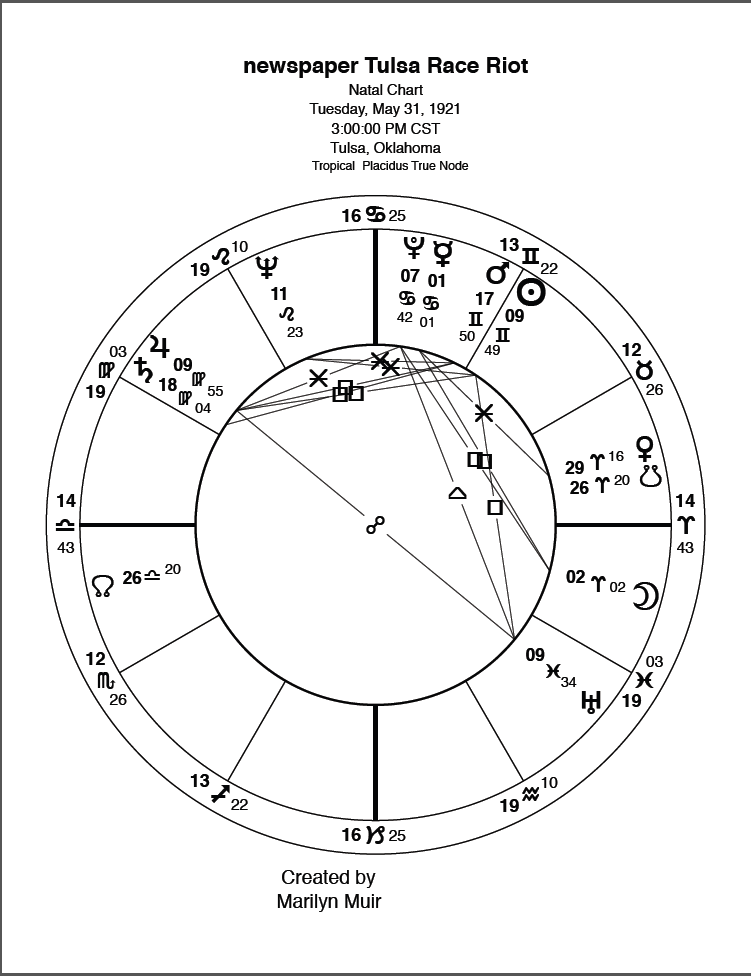

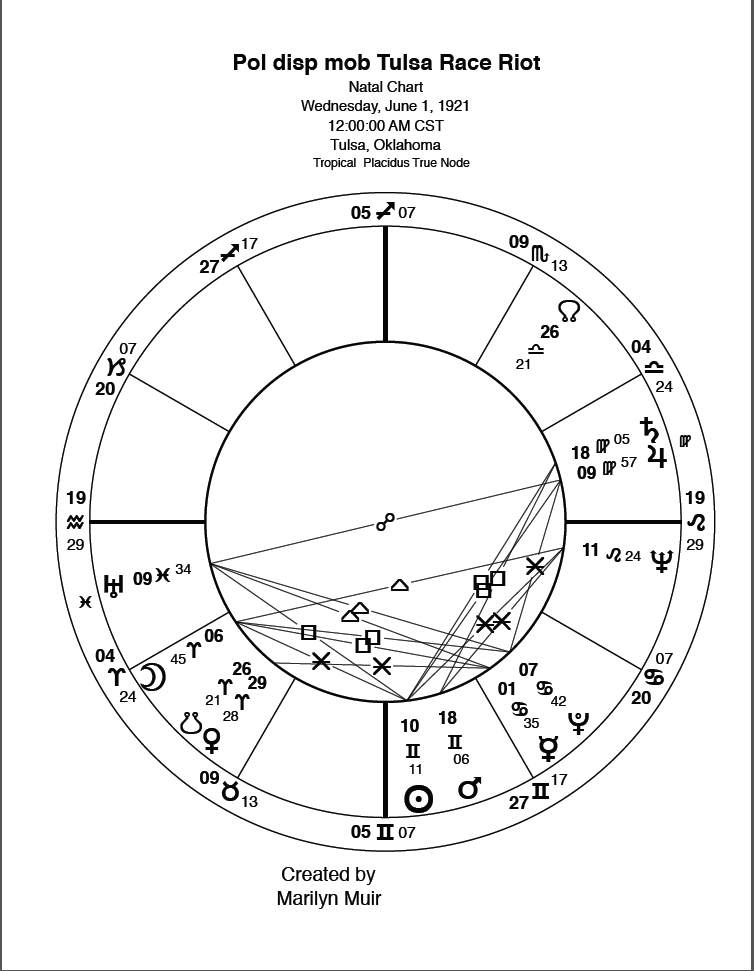

- Plus seventeen Tulsa race riot timed event charts: 1st shot, 30 blocks burned, 75 blocks burned, authorities alerted, elevator, fires set, hostilities stop (???), inferno, National Guard 1 and 2, newspaper, police disperse mob, suspect arrest, train whistle, turn three away, white mob, martial law

From my notes, my friend, Astrologer Jackie Chakhtoura, helped me find various pieces of this information and I want to acknowledge her assistance. I was also able to figure out that what held me up from completion in 2015 was the reported aerial bombing of the Greenwood tragedy, which at the time I was unable to pin down. As I was assembling this work to post on the website research pages, President Joseph Biden gave his commemorative talk about this tragedy. He mentioned specifically the aerial bombing of Molotov cocktails and other incendiary devices onto the defenseless residents. While I do not have a specific time for that, President Biden is a credible source that the aerial attack did occur as reported. There is a plethora of material available currently – simply Google for it. There may be updates.

I would like to know what you find and develop from this material.

Other notes from earlier research:

Tulsa 1921 massacre search for graves https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KkTDytp2VBIhttps://www.cnn.com/2019/10/21/us/tulsa-race-riot-black-wall-street-watchmen-trnd/index.html

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.